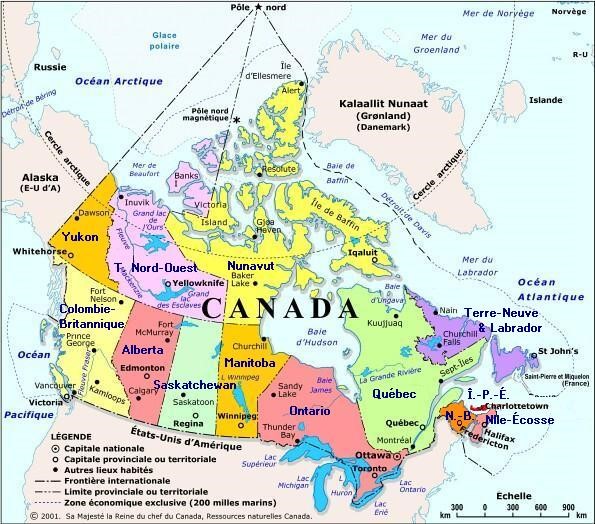

The Home page provides an overview of Canada's geopolitical situation: some basic information and notions of the Canadian federation that help to understand Canada through its geographic, legal, administrative and demographic circumstances. You will also find the relevant information about how to use and quote the CLMC.

The section Political and Institutional Foundations of Linguistic Planning in Canada, created by Professor Linda Cardinal, helps to understand the political concepts of linguistic regimes and federalism, while also presenting the elements of Canadian language policy.

The Linguistic History of Canada section was written by Professor Jacques Leclerc. It is a voluminous section that provides a wealth of information about languages in Canada, from the first languages spoken by Aboriginal people to the introduction of English and French. It then traces the Franco-British rivalries that have laid the foundations for the status of languages, and have contributed to the formation of modern Canada. This section explains how, progressively, demographics have changed until the country became predominantly English-speaking, especially after the American Revolution and the arrival of the Loyalists, and then the arrival of hundreds of thousands of immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries. Finally, it deals with the introduction of official bilingualism in Canada in 1969 and the advent of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, which resulted in considerable progress in the protection of linguistic rights and in the equality of the two official languages. This section also includes an inventory of historical documents and an extensive bibliography. It covers the history of language management from the origins of Canada to the dawn of the 21st century.

The Legal Framework section, authored by Professor François Larocque, explains how the jurisdiction to legislate on language is shared between the various levels of government (federal and provincial / territorial). You will also find numerous hyperlinks to constitutional, federal, and provincial / territorial legislation, as well as to the key judgments that shaped Canada's language management.

The Language Rights section comes from the former LRSP site, as previously explained. It is complementary to the Legislative Framework as it also addresses the legal aspects of language planning in Canada. It takes a pedagogical, rather than scientific or legal angle. It explains the rights and protection measures for members of official language minorities, whether in the field of communications and services, in the judicial and legislative spheres, or in education. It includes, among others, impact studies, case studies, resources for official language minority communities, and fact sheets for secondary schools.

The section on Demolinguistic Statistics was written by Jean-Pierre Corbeil and Alejandro Paez Silva from Statistics Canada in order to guide the reader through some 40 linguistic surveys conducted since 1901 (the date of the first census including linguistic questions) by Statistics Canada. In particular, this section presents 1) the history, development, and conceptualization of language variables currently used by Statistics Canada; 2) the different sources of data available and their different characteristics; and 3) some of the most relevant publications and data tables, whether through hyperlinks or PDF documents.

The author of the Governance section is Carsten Quell, Executive Director at the Center for Excellence in Official Languages, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. This section reports on the diversity of language governance models in 14 Canadian jurisdictions (one federal level, three territories and ten provinces).

The final section, International Perspective, places the Canadian model of language planning on the international stage. Created by Professor Jacques Leclerc, author of the Aménagement linguistique dans le monde (website in French only), this section shows how Canada compares and distinguishes itself from some other officially multilingual countries, in terms of both territorial rights and collective rights.