Gazette

Stories and news from across campus.

Ending the Drought: Ottawa’s Medical Research Community Welcomes Long-Awaited Wet Lab Facilities

Most people only think about their metabolism when their pants get too tight, blaming weight gain on their metabolism slowing down.

The University of Ottawa’s new Advanced Medical Research Centre will accelerate discovery and new treatments

The rapid development and deployment of vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical role of research in creating lifesaving medical…

If you build it, they will stay: Ending Ottawa’s biotech brain drain

Ottawa has earned its global reputation as a vibrant city for medical research and innovation. But if it wants to keep its intellectual capital in the…

University of Ottawa joins the race for the commercialization of betavoltaic batteries

Batteries running for decades without recharging: Dream or near-future reality?

Sticking to innovation: The surprising role of tape in terahertz photonics

Could the key to next-generation photonic devices be hiding in your drawer? For Professor Jean-Michel Ménard, an ordinary roll of tape proved essentia…

Turning data into equity: How two researchers are reshaping the music industry and community services

What do country music charts and non-profit training have in common? At first glance, not much. But in the hands of uOttawa professors Jada Watson and…

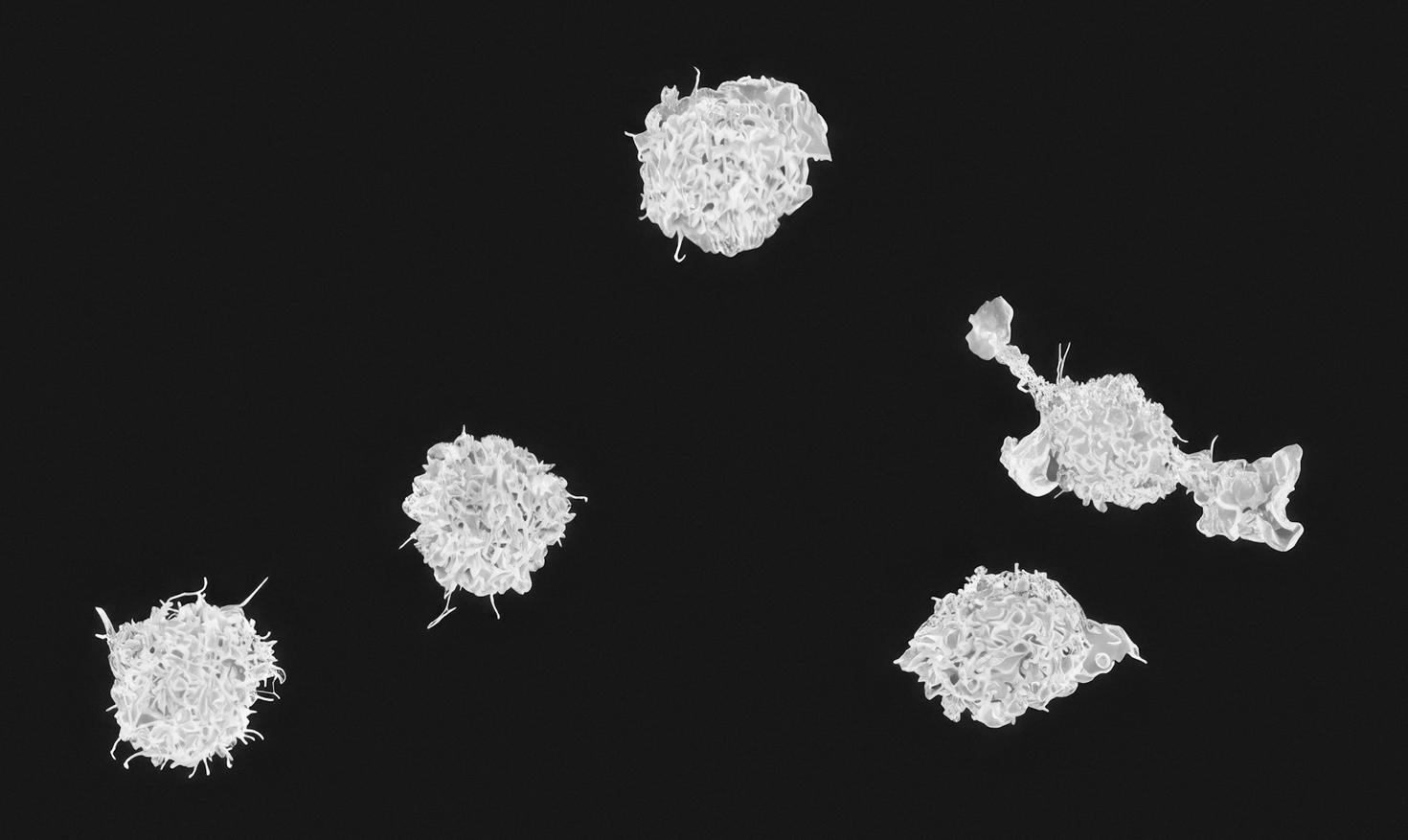

uOttawa Medicine scientists zero in on cellular mechanism fueling drug-resistant cancers

A Canada Research Chair's uOttawaMed lab unveils promising new insights underlying cancer treatment resistance, perhaps paving the way for enhancing t…

Engineering ultra-thin magnets to power next-gen electronics

A team of international researchers led by the University of Ottawa has made a breakthrough in the development of ultra-thin magnets—a discovery that …

How eulachon grease links generations, culture and cutting-edge science

In the coastal First Nation communities of British Columbia, the return of a small, silvery fish each spring marks much more than a seasonal cycle. Fo…

Aug 27

to

Sep 5

Information Tent

We look forward to welcoming you and to helping you start your uOttawa experience off right. …

Aug 29

Free Store Pop-Up

Check out the free, environmentally responsible finds at the uOttawa Free Store!

One step closer to a nature-positive campus

This week, uOttawa took another step toward fulfilling its Nature Positive Pledge as well as its commitment to restoring green spaces for biodiversity…

Arts District: A creative public space in the heart of a university and city of culture

The Faculty of Arts is a world bubbling with culture and ideas. Languages and literatures, humanities, fine and performing arts — all open the door to…

uOttawa grows Kanata North’s presence to meet rising innovation demands

New campus space at 350 Legget anchors research, innovation, and talent where the industry needs it most.

Where to eat on campus

Hungry? You don’t have to leave campus to eat the best food around! Discover all the yummy spots to choose from and get insight into the latest food d…

10 student clubs to discover

Whether you love to sing, dance, help others, hike or build rockets, there’s something for everyone when it comes to the 279 student clubs at uOttawa.…

A new way to register for recreation and fitness activities

Gee-Gee Reg is the University of Ottawa’s new registration system for recreation and fitness services, now powered by ACTIVENet. This platform allows …

Shana Poplack receives the Award for Research Excellence in Francophonie

It is well known that in Canada, countless spirited debates revolve around official languages and their authenticity and resilience.

“Does mixin…

“Does mixin…

The Faculty of Law contributes to the translation of historic Supreme Court decisions

In its commitment to promoting bilingual access to landmark decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada, the Faculty of Law has contributed to a major pr…

A look back on CCERBAL 2025 and Carrefour francophone

Two major events this spring featured several opportunities to quench your thirst for knowledge and to connect with peers.

Not just a messenger: Developing nano-sized delivery agents that also provide therapeutic treatment

University of Ottawa researchers show particles can not only deliver doses to complex diseases but also contribute to treatment

Photonics for health care: a new laser for biosensors

PhD student Shayan Saeidi is developing a compact, affordable biosensor that could improve how we detect health conditions in fluid samples.

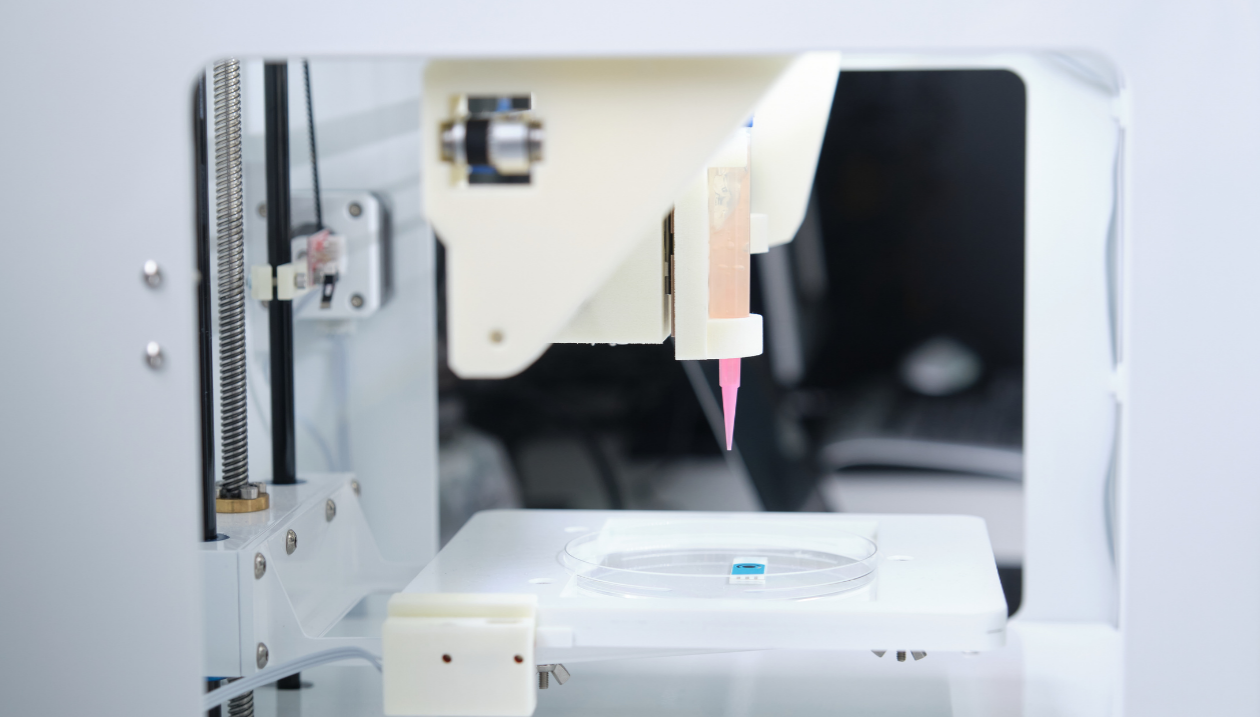

3D printing living tissue: from joint pain to osteoarthritis

Biomedical engineering student Olivia Steiner is developing smarter bioinks to improve 3D bioprinting for tissue engineering — with big implications f…

True North Berries: Turning winter white into strawberry delight

Professor Allyson MacLean is leading an ambitious project to grow fresh, locally produced strawberries — even in the dead of winter. Supported by a $1…

Oceans are losing their breath: Understanding the effect of hypoxia on fish immune systems

Discover how Professor Matthew Pamenter is working with experts from Australia and New Zealand to conduct pioneering research on how hypoxia impacts f…

From academia to industry: Inspiring stories of uOttawa startups

The Faculty of Science is creating a framework that facilitates the transformation of innovative academic ideas into real-world businesses. Through la…

The hidden costs of being a woman at work

As a renowned professor of psychology in the industrial-organizational program at Pennsylvania State University, Dr. Grandey took the stage at the Tel…

Entrepreneurial women: Olga Koppel’s quest for cleaner cities

“Pivoting is the one constant in starting a business.” That’s how Olga Koppel describes her journey from academia to entrepreneurship.

CEO Magazine ranks Telfer the #1 global executive MBA and a tier one MBA

Ottawa, ON – The Telfer School of Management proudly announces that its graduate programs have once again secured top recognition in the 2025 CEO Maga…

Conversations for reflection: Amplifying 2SLGBTQI+ voices and mental health

The moment Sarah Hobson (MA '25) picked up the textbook in her high school psychology course, she had a feeling her career path would somehow lead to …

Guadalupe Escalante Rengifo: Teaching that connects and transforms

For Professor Guadalupe Escalante Rengifo, teaching is not a one-way transfer of knowledge — it’s a dynamic, reciprocal act of learning.

What a study about prison theatre reveals about rehabilitation

In a makeshift theatre inside a federal prison on Vancouver Island, incarcerated men adjust lights, paint backdrops and rehearse lines.

Microaggressions and mental health: What racialized students are telling us

Across Canada, racial microaggressions, those everyday slights or assumptions that may seem minor but carry a heavy emotional weight, are increasingly…

Professor Douglas Sarro investigates the law behind financial innovation

As cutting-edge technologies reshape financial markets, Canadian households stand to benefit from more accessible, lower-cost, and higher-quality fina…

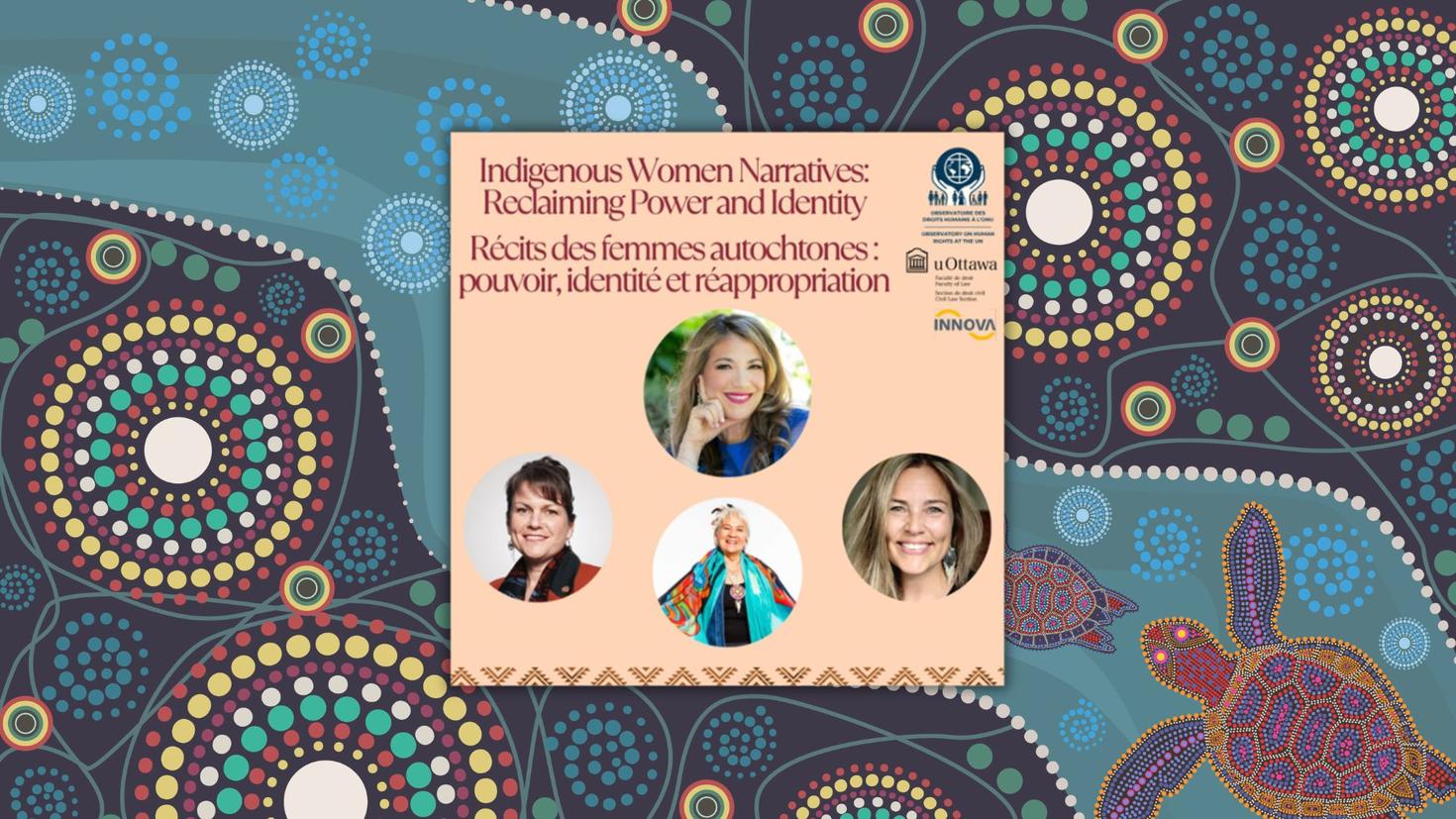

Professor Pascale Fournier leads a new partnership addressing the Indian Act’s legacy of discrimination

For over a century, the Indian Act has defined – and too often denied – Indigenous identity. A bold new research partnership is taking aim at this leg…

Faculty news

Contact us

Gazette news

Tabaret Hall

550 Cumberland Street, room M284

Ottawa ON K1N 6N5

Canada

Tel: 613-562-5800 extension 5708

Fax: 613-562-5117

[email protected]

Submit your story

Have ideas for story? Want to get your initiative out there? Reach out to our team to submit your story at [email protected].