The majority of the workers at Puretex were immigrant women; most from Italy, others from Portugal, Greece, and the Caribbean.

The Puretex strike would later be described by scholars as a “flashpoint” around which Canadian feminists rallied to support and mobilize exploited immigrant women in the textile industry.

But there is much more to this story.

In fact, as historians who have delved into the Canadian Women’s Movement Archives have demonstrated, that strike was one important event in a crucial and ongoing transformation of the mainstream women’s movement, that was led by immigrant women themselves.

Feminist historian Julia Aguiar is among those who have connected the dots between labour conflicts like the one at Puretex, an organization called Women Working with Immigrant Women (WWIW), and the push toward more diversity in the women’s movement.

“Women Working with Immigrant Women was a central fixture of immigrant women’s organizing,” writes Aguiar in her 2022 master’s thesis on the topic.

The demographics of Canadian immigration changed dramatically after 1967, when a new “points system” came into play that promised to put an end to the practice of choosing immigrants based on their race and nationality. The proportion of immigrants from Europe dropped significantly, while those from Asia, the Caribbean, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa increased.

In response to this new influx, many service organizations sprang up in Toronto and other Canadian cities throughout the 1970s that were geared to the needs of immigrant women.

WWIW was founded in 1974 by a group of women working with various service agencies serving immigrant communities in Toronto. They saw the need for an umbrella advocacy group that could network and lobby specifically for immigrant women and build networks between them and other progressive movements.

Appropriately, immigrant women took over the leadership of the organization soon after WWIW was founded. Many of these women had come to Canada from countries ruled by authoritarian regimes and so were not new to feminism nor to political activism.

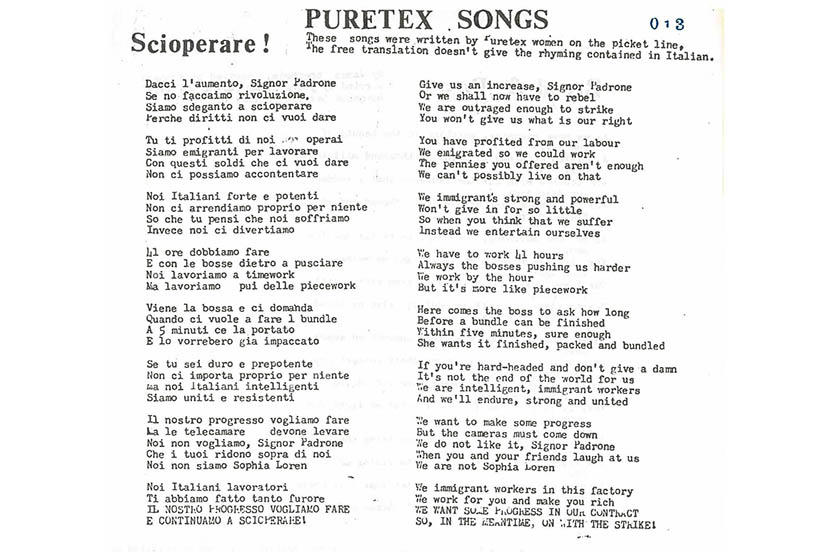

Many immigrant women were employed in the textile industry in this period, so WWIW reached out to their unions. Some of the women involved in the labour strife at the Puretex Knitting Company joined WWIW, including Salomé Loucas.

Loucas had moved to Toronto from Cyprus, Greece in 1969 when she was 20, sponsored by her romantic partner who had arrived earlier. She got a job as an unskilled labourer at Puretex just a few weeks after her arrival, making $1.10 an hour. After her two children were born and her relationship with their father ended, she needed to find a way to earn more.

“I became a cutter and then I started to realize that the men cutters were making more money than we were making,” Loucas said in an interview from her home in Toronto. “That’s when I really got involved with the union to try to change that and other things.”

I was a single mother at the time…And it’s not like when you go to the store, they give you groceries for less money because you are a woman. You have the same expenses, and every penny counts.”

The Puretex workers voted to join the Canadian Textile and Chemical Union in 1972. Loucas remembers working closely with legendary Quebec feminist and labour activist Madeleine Parent to get Puretex workers unionized. Parent was co-founder of the CTCU and secretary-treasurer of the union at that time, and a high-profile ally of textile workers during their many battles with management throughout the 1970s and early 80s.

The Puretex workers went on strike for the first time in 1972 to put pressure on the employer to sign their first contract. That won them a slight wage increase and a 45-hour work week, but the wage gap between male and female workers remained, and labour relations worsened over ensuing years.

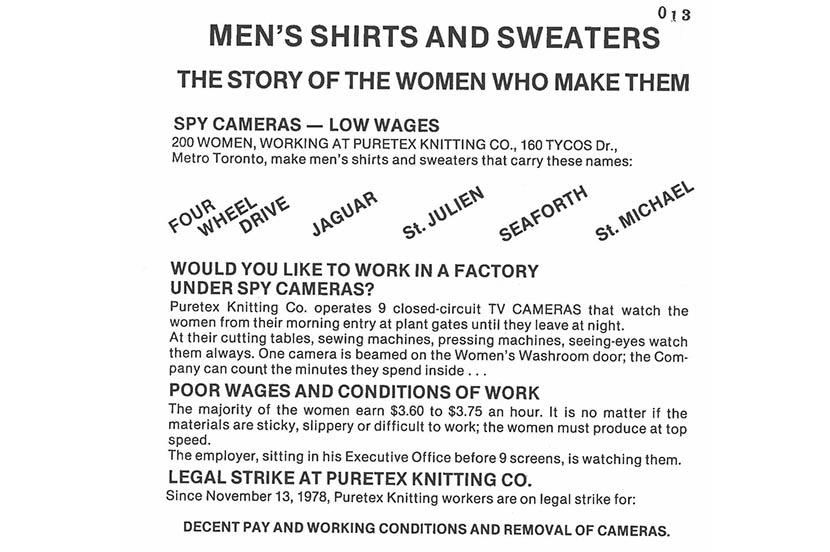

In 1976, the Puretex workers complained to the media and the Ontario Human Rights Commission about their working conditions.

The factory owner had installed nine closed-circuit television cameras around the plant, which monitored the female workers’ every move, with one camera trained directly on the door of the women’s washroom. Men were employed only in the afternoon at the plant and the cameras were not switched on during that shift, nor was the men’s washroom door monitored.

In an interview with CBC radio in the spring of 1977, Parent said, “It’s unworthy of human beings that they should be scrutinized by cameras all of the time.”

Puretex owner Gary Satok claimed the workers were stealing from him, but in arbitration, he could only point to one serious incident of theft by an employee, who had been fired, charged and convicted.

“I’ve got to see where my people are all day,” Satok told the Globe and Mail by way of justifying his surveillance practice at the time. “I don’t have time to waste fooling around. How the hell am I supposed to run this place unless I know everyone’s doing their job?”

As they fought for better working conditions and better services, immigrant women were becoming increasingly politicized and organized. Soon, provincial and national organizations sprung up, like the Coalition of Visible Minority Women, the Organization of Immigrant and Visible Minority Women of Ontario and the Organization of Immigrant and Visible Minority Women of Canada. Members of WWIW played an active role in all these groups.

In 1978, Canada’s first International Women’s Day rally was held at the University of Toronto’s Convocation Hall, with about 2,000 people in attendance. One of the speakers was Sherona Hall, of the Committee to Defend Jamaican Mothers. Hall’s speech got the media’s attention as well as the attention of the organizers of the rally. The unfair deportation of Jamaican mothers working as domestic helpers made it to the list of focus issues of the next Women’s Day rally.

But Carolyn Egan, an early member of WWIW and of the March 8 Coalition, which organized International Women’s Day, explains that in those early days, feminists didn’t yet see racism as a women’s issue.

"They weren’t stereotypical middle-class women,” Egan said. “They were downtown people who were politically involved. But consciousness was a developing thing and when you talk about (women’s issues), whether it be childcare or workplace issues or whatever, you have to have the voices of diverse communities on stage. That was a learning process that took place and it was important. Very, very, very important.”

That process gradually bore fruit, and immigrant and racialized women began to move into the forefront of the women’s movement. In 1979, for example, the Puretex strikers led Toronto’s International Women’s Day march.

In 1981, WWIW joined the March 8 Coalition officially, and since that time, immigrant women have played a prominent role in every International Women’s Day in Toronto.

Loucas took over the role of coordinator of WWIW in 1984, after Puretex closed its factory. She would remain in that position, the only paid position at WWIW, until it folded in the mid-2000s.Loucas had pushed for the WWIW to join mainstream feminist organizations like the National Action Committee on the Status of Women.

“It was a very big deal because nobody wanted to join the mainstream movement,” Loucas stated. “They said, ‘They haven’t done anything for us so why should we join?’ And I said we should get involved. I mean, there was nothing wrong with organizing amongst ourselves, but at some point, we were going to have to join the mainstream to get the support we needed.”

Judy Vashti Persad, who joined WWIW a couple of years after Loucas took over, recalls the mid-1980s as a very exciting era of the women’s movement. WWIW was playing a key role in what she calls an “alternative women’s movement”, working hard to bring the voices of immigrants, women of colour and women living in poverty to the fore.

“WWIW made the conscious political decision to work within the immigrant and women of colour communities, but also work with broader movements such as the women’s movement and the labour movement…because we saw that to really create…systemic change, it was important to join with other progressive movements,” Persad said in an interview for a series on the history of the Canadian women’s movement created by the Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive.

“And yes, there were challenges within those movements…but we made the decision to be a part of it and work within it to change the structures, policies and practices within it…to advocate on a larger collective level.”

Within the NAC, Loucas and others pushed for the creation of a new committee, the Visible Minority Women and Immigrant Women's Committee, which played a key role in raising awareness about racism and privilege in that organization.

Loucas doesn’t recall resistance, per se, but it took time for some in the mainstream movement to stop seeing the challenges immigrant and visible minority women faced as somehow side issues to the women’s movement.

Immigrant women wanted support in their demands for English as a second language training, for example. At the time, the government provided financial support for “heads of the family” to learn English full time, but language courses for women were only offered in the evenings.

“There were evening classes offered, but if you think of how most of us were working, there was no way that I could stand for eight or ten hours a day at the factory, from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., and then come home and go to an evening school.”

Immigrant women also had different perspectives on childcare.

“Different women were affected differently and I’m talking about his from personal experience. For example, I had two very young children and I needed to be at work at 8 a.m. Most of the daycares at the time didn’t open until 7:30. And my kids were three years apart, so I actually had to take them to different centres. So, to be able to get to work on time, I had half an hour and I had to take, like, three different buses.”

Immigrant women also wanted to see the movement focus not only on abortion rights, but also on attaining equal pay for working women so they could support the children they had or the ones they wanted.

“So, you have to address all these different issues, whether you’re dealing with reproductive rights, or whether it’s childcare or equal pay. Whatever the issue is you also have to know how it’s affecting all the different groups,” said Loucas.

She acknowledges that getting the white and wealthier women in the mainstream of the women’s movement to be sensitive to the needs and issues that affected immigrant women and women of colour was not always easy. But she doesn’t recall there being “resistance” per se.

“I never thought it was a malicious kind of thing, you know, with people saying, 'how are we going to exclude you?’ It was more about getting them to understand us and work together.”

Once the WWIW and other immigrant and racialized women’s groups joined the NAC and the March 8th coalition, the dynamics of the movement began to change.

“It’s not that there weren’t women of colour (in the movement) prior to that, but it made a big difference,” Egan said.

The women who were active in the mainstream movement “came from a political perspective,” said Egan. “They appreciated that to make change in our society you need a broad-based movement, a movement that was very representative and diverse and had the power to bring a lot of people into the streets, the power to bring pressure to bear on the various levels of government to get the services we needed. …That sense of collective strength was very much the politic of Women Working with Immigrant Women.”

WWIW collaborated with other organizations on several ground-breaking projects in the mid-1980s, such as an Ontario-wide immigrant women’s forum in 1985. They lobbied for years for funding for the first shelter for immigrant women escaping violence, Shirley Samaroo House, which opened in 1986.

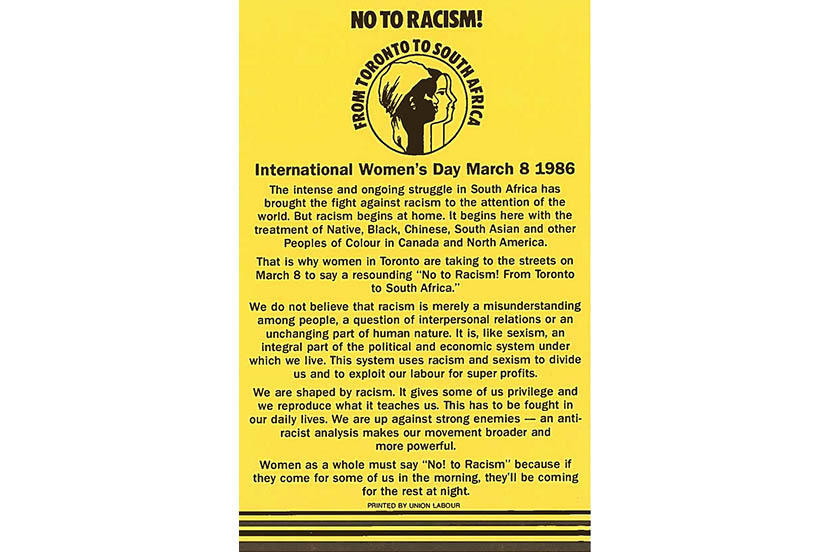

But even as progress was made on some issues, the broader women’s movement had still not grasped the interconnected nature of sexism, racism, classism, and anti-immigration discrimination.

“In 1986, racism was still not seen as a major concern for the women's movement,” Persad said in the Rise Up! interview. “And, yes, issues had been covered but when you look at who determined the political direction of the March 8th Coalition, it was still white women. And when women of colour were chosen as speakers or if they participated in the coalition, it was the ‘Native’ woman or the ‘Indigenous’ woman, the ‘Black’ woman, the ‘South Asian’ woman and it was always the other. Still, we were the ‘other’.

“And this needed to change. I mean if the women's movement was to be a movement to represent all women, there had to be change. It had to reflect and incorporate the lived realities of all women, the lived realities of Indigenous women, of Black women, of South Asian women.”

So that year, WWIW led an initiative, along with the International Women’s Day Committee, to make racism the focus of Toronto’s International Women’s Day events.

They made a proposal to the March 8 Coalition, that instead of producing a list of issues and themes for Women’s Day as usual, the focus of the 1986 event would be racism and only racism.

The proposal read, “It is time for the feminist movement to recognize in a very public way that the struggle against racism is our struggle. We hope to use March 8th, 1986, to make a resounding statement about this. For this reason, the coalition must lead the way in efforts to build the feminist movement on an even broader basis and to bring the issue of racism to the attention of the coalition's component groups. We think it is time to put the issue of racism front and center. We propose that the central theme for March 8th be women saying, ‘No to Racism from Toronto to South Africa’.”

That focus helped attract many more women of colour and immigrant women to the movement, Persad said.

In March of 1990, the WWIW, along with the Visible Minority and Immigrant Women Committee of the NAC, and the Cross-Cultural Communication Centre, put together a handbook entitled “Towards a Non-Racist Women’s Movement”.

The handbook is a clearly written, 17-page document that includes definitions, exercises and resources designed to help the NAC and its member groups identify and fight racism within their ranks. The introduction explains the issues succinctly:

“The Women’s Movement has historically focused its attention on the concerns and issues of white women, with emphasis on sexism and all that the term implies. Sexism has been seen as the primary cause of women’s oppression and the barrier to equality and empowerment of women. For women of colour and immigrant women, while sexism is part of their oppression, racism has been a major cause, but little attention has been accorded to it within the movement.”

Loucas and Persad collaborated on several ground-breaking research projects sponsored by WWIW, including “Through the Eyes of Workers of Colour: Linking Struggles for Social Justice” and “No Hijab is Permitted Here; A Study on the Experiences of Muslim Women Wearing Hijab Applying for Work in the Manufacturing, Sales and Service Sectors”.

In 1994, WWIW officially took over the organizing of Toronto’s International Women’s Day march and rally. And although WWIW closed its office in the mid-2000s, its executive still comes together every year to organize that rally and march, which is among the largest and most diverse women’s marches in the world.