The two young women had been writing for a new feminist newspaper called The Other Woman, and reading a lot of exciting literature at the recently-opened Toronto Women’s Bookstore. They felt compelled to spread the news about the burgeoning women’s movement beyond the big city.

“I don’t know whose idea it was in the first place, but we’d been becoming aware, from the stuff coming into the paper, that the world existed outside of Toronto,” says Quinlan. “In the beginning, a lot was happening in the big cities but there were women in small towns who were totally cut off…They were experiencing all of the kinds of things we were fighting against. Like, if their husbands died, they wouldn’t get any money… or if they wanted an abortion, they could never get one. So, we decided we wanted to connect with the small towns and because the bookstore was starting, we thought, ‘Well, we’ll take the bookstore to the small towns.’”

So, they applied for a government grant and used it to turn an old school bus into a mobile library. They installed a couple of seats facing each other in the front, some magazine racks and book bins, and a bed in the back. They christened the bus Cora, after early suffragette E. Cora Hind, and spent two summers driving all over rural Ontario and into Quebec. They would park the bus wherever people were – parks, fairgrounds, town centres – and put an “open” sign in the window. Sometimes nobody came, says Quinlan, and sometimes “there would be hordes of women” and the occasional man, boarding the bus to browse and chat.

A black and white photograph from that summer shows a young Quinlan, hands on hips in wide-legged denim overalls, standing behind the bus, with Woodsworth and another young activist named Boo Watson. They are all smiling broadly. “Women’s liberation bookmobile” is painted in bold, sans serif lettering on the side of the bus. A handwritten sign taped to the back window reads “Wages for Housework”.

You can find this photograph in the Women’s Archives in the uOttawa’s Morisset Library, along other memorabilia from the bookmobile, the newspaper, and the bookstore. In fact, you can find the records of over 350 grassroots organizations and initiatives in the Women’s Archives collection, the personal papers of hundreds of Canadians involved in what would become known as “the second wave” of the woman’s movement, and the largest collection of feminist publications and newsletters in Canada, with over 1,400 titles.

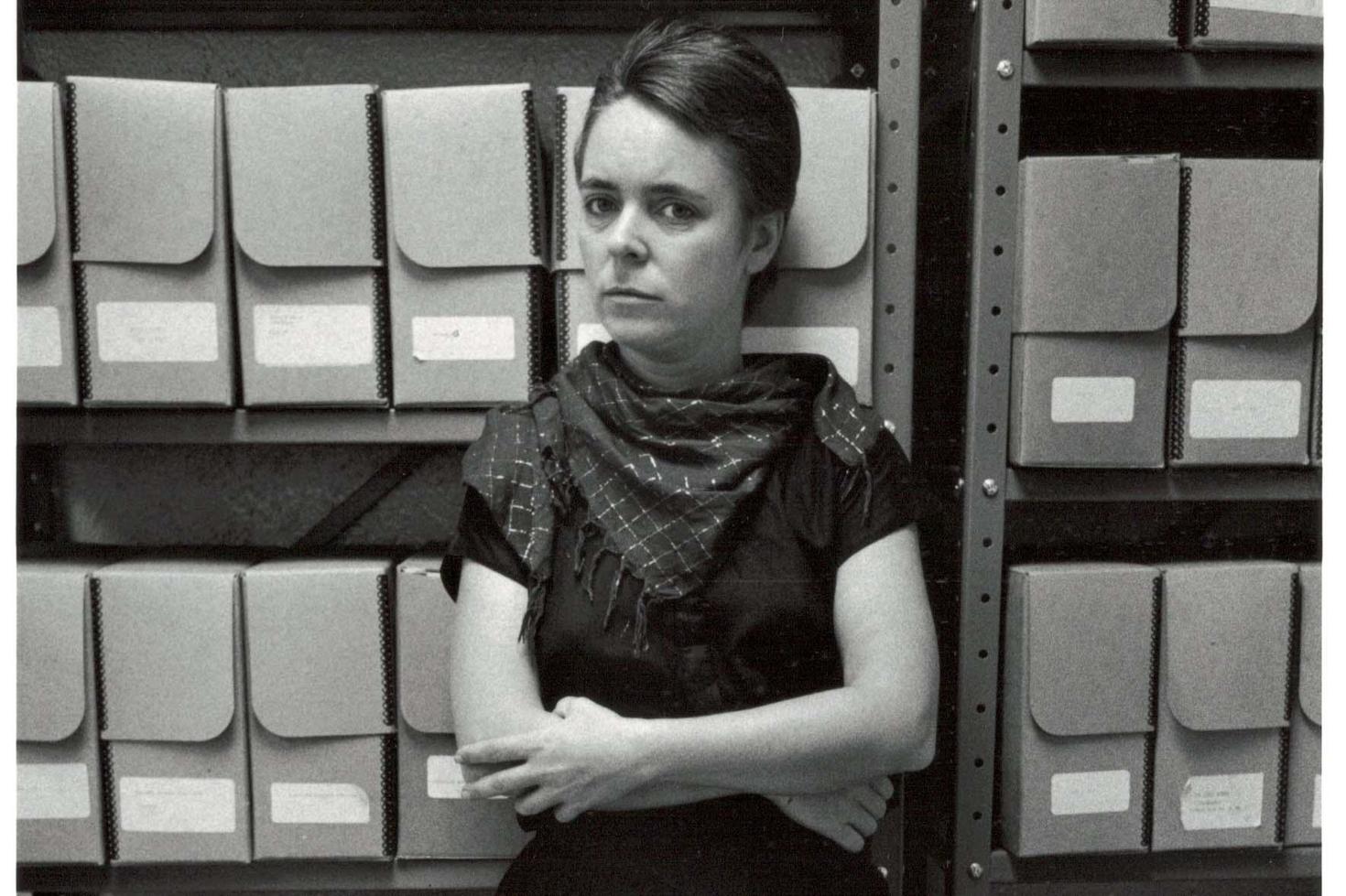

This astoundingly rich and diverse collection was initiated by Pat Leslie, editor of The Other Woman newspaper. When that publication was winding down in the late ‘70s, Leslie and her colleagues decided to keep its editions and records, as important artefacts of the women’s movement. They wrote to other feminist news outlets and organizations across Canada, requesting copies of their publications and records.

“A document is something more than a sheet of paper,” Leslie wrote in 1980. “It is a very alive piece of herstory. Must we allow our daughters to suffer the same mistakes as ourselves because we neglected to provide a continuity of ideas? Keeping ‘useless’ pieces of paper is never a waste of time. Nothing, nothing which relates to our movement should be thrown away.”

In 1983, by which time the collection had outgrown Leslie’s apartment, a group of women interested in expanding and cataloguing the collection joined Leslie and her team to form the Canadian Women’s Movement Archives collective. That group raised funds and moved the collection to a rented space, where it could be made available to researchers. In 1992, the CWMA collection was donated in its entirety to the University of Ottawa Library.

Gathering and preserving records of the second wave, which surged from the late ‘60s to the early ‘90s, was and remains a tall order. The “wave” was actually hundreds of thousands of grassroots actions by individuals and groups across the country. Without the convenience of cellphones or the internet, these feminists were creating a tsunami of awareness one meeting, one march, one fundraiser at a time. They were holding consciousness-raising sessions, opening women’s centres and shelters, founding advocacy groups, writing newsletters and generally rabble rousing, all in a post-war culture that was hostile to women who spoke too loudly or asked for too much.

“We were debating the state of the world and plotting how to make change, and we were sewing”

Nancy Adamson

Nancy Adamson was a PhD student in history at the University of Toronto when she joined the CWMA collective in 1983. As an activist herself, Adamson felt it was important that women’s voices outside of academia and government be archived.

“What makes the Canadian Women’s Movement Archives special is that it tried to reflect the movement whose records it was collecting,” she says.

Sometimes that meant keeping, for example, a scrap of paper that referred to one event organized by women in a small town in northern Ontario. Files were not discarded if they were incomplete or contained only one document; the collection was designed to be continually expanded.

“We collected every scrap of information we could find about women’s organizations. We kept it, we catalogued it under its group name and it’s there now at the University of Ottawa for anyone to see and read those stories and discover all the activity that was taking place in the second wave of the women’s movement,” she says. “Well, not all,” she adds, but even a scrap of paper might offer a “hint of where to go if you want to learn more”.

What Adamson prizes most about the CWMA collection, besides the unconventional way it came together, is the tactile nature of some of its holdings: the banners and T-shirts and buttons. She recalls a gathering in Toronto in the early ‘80s where members of the International Women’s Day Committee sewed a banner, now part of the collection.

“We were debating the state of the world and plotting how to make change, and we were sewing,” she says. “I think that challenges this way that people stereotype feminists, or at least did in that time, that we were militant and harsh and hard. And we could be those things, sure, but we could also sit around and have a quilting bee to make our banners. I like that it shows that; all the many sides of who we were, whether we held bake sales or marched on Parliament. We could do all those things.”

Those tangible relics – the slogan buttons, banners, educational kits, pamphlets, recordings of speeches, oral histories, videos and more – are key to preserving the true grassroots nature of the movement, says Margaret McPhail, a former teacher, union organizer and women’s rights activist.

“The practice of archiving is traditionally very narrow,” says McPhail. “Who saves their records? People who think they are going to be important and have the room and the where-with-all to do it. So, capturing this kind of ephemera, if you like, adds a whole new dimension to our understanding of the roots of and role of and power of the second wave women’s movement. It is important to understand its history as a movement, not as the result of – and not to diminish their individual roles – five or six or ten important women.”

McPhail is a founding member of Rise up! a volunteer-run, digital archive of feminist activism, which she considers a complementary initiative to the much larger physical and digital Women’s Archives collection held at the uOttawa Library. The aim of both archives is “to preserve the activities of diverse grassroots feminist activism across Canada, including voices that are often absent, such as those of lesbian activists, Indigenous women, racialized and black women, immigrant women. So it reflects that diversity, because the Canadian Women’s Movement Archives originally was grassroots built.”

McPhail says the second half of the 20th century was a fertile time for social justice movements and there was much cross-pollination. Her own activism began in her late teens, when she became involved on the socialist left. She later joined the International Women’s Day Committee, a coalition of socialist feminist groups.

“The time was right,” she says. “The feminist movement was growing, the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement...all these kinds of things were happening in terms of challenging oppression... It just was a period of burgeoning political questioning and activism that intersected with equality rights whether it was anti-colonialism, Indigenous persons activism...Quebec separatism, all that stuff...It was like an explosion of activism and consciousness among women across the country, in large cities and smaller communities, and very grassroots. From almost nothing, it seemed like overnight there were so many things happening”.

Janet Torge, co-founder of Canada’s first rape relief centre in Vancouver, says feminists like herself in the early ‘70s tended to be involved in many different struggles at once, and the personal fed the political. People were physically connected in a way that is not as common today, often living in communal settings, and that helped spread the seeds of rebellion, Torge contends. “You got involved in one thing, and that led you to another thing.”

As a member of the Vancouver Women’s Health Collective, Torge remembers participating in a consciousness-raising session on sexual assault in 1973 where most of the participants shared that they had been raped. Torge and two other women from the collective – Johanna Den Hertog and Teresa Moore – decided to create a service that would accompany and support rape victims through the court process.

“The first thing we were dealing with was this attitude that there was no such thing as rape because (the thinking was that) a woman could just walk away,” Torge says. She recalls a trial she attended where the defense lawyer tried to demonstrate this by asking the complainant to come down from the stand and hold a coke bottle. He then asked her to avoid letting him put a pencil in the bottle. “That was how they (tried to show) there was no such thing as rape. The only way rape could happen is if she stood there and allowed the guy to put the pencil in the Coke bottle…They (lawyers, police, judges) had no concept of the fear.”

There was a lot to rebel against at the time, Torge recalls, but young people had the impression they could change the world. Another factor feeding the movement, she says, was the availability of government grants like Local Initiative Programs (LIPs) and Opportunities for Youth (OFYs), so young people could get by financially while working for social justice causes. Travel was cheap, especially if you hitch-hiked or hopped on a motorbike, and young activists were mobile.

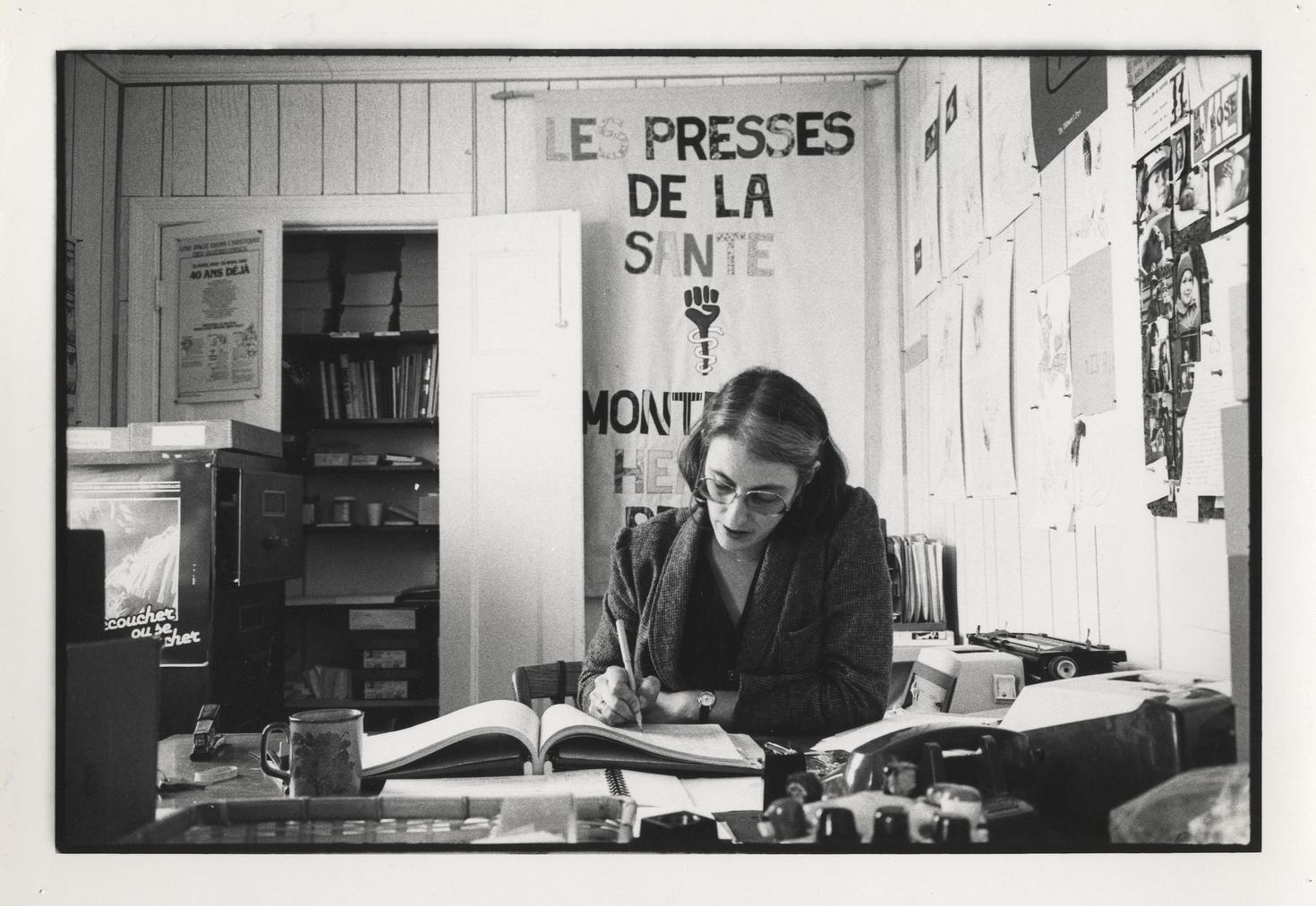

“Life was very fluid back then,” says Torge, who moved to Montreal in 1975 and worked for the Montreal Health Press, a feminist, non-profit collective that published handbooks on sexuality and sexual health, including the famous and initially illegal, Birth Control Handbook. Torge went on to write a handbook on sexual assault for the MHP collective, which distributed millions of copies of its various publications between 1968 and 2000. Many of these are preserved in the Women’s Archives.

“When I became president of NAC there were 550 groups; everyone from the Women’s Temperance League to the Women’s Committee of the Communist Party of Canada. It was amazing. There were tons of debates...”

Judy Rebick

Judy Rebick agrees that the in-person nature of networking at the time, as well as the interconnectedness of movements on the left, fueled the second wave.

“We did it all in person,” says Rebick, who was active in New Left and pro-choice movements before serving as president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC) in the early ‘90s. “And the advantage of doing it in person is you made connections in a way you don’t in the same way online. So you feel more committed to it.”

The interaction between the union movement and the pro-choice movement is one example of how women in different progressive movements collaborated to make change. Women’s groups picketed with striking female workers, and unions provided protection at abortion clinics.

“The whole history of the unions and feminism was really important in Canada,” says Rebick. “That didn’t happen in the States and it didn’t happen in Europe. In Europe, the unions were involved in the political parties, but they weren’t involved in the women’s movement at all.”

Despite these kinds of collaborations, second-wave feminists were far from united on all fronts. There were clashes between socialists and conservatives, lesbians and heterosexuals, those who wanted the movement to focus on “free abortion on demand” and others who wanted as much emphasis on equal pay and childcare so they could afford to raise the children they wanted.

“When I became president of NAC there were, I think, 550 member groups; everyone from the Women’s Temperance League to the Women’s Committee of the Communist Party of Canada,” says Rebick. “It was amazing. There were tons of debates…We had what we called Roberta’s Rules of Order. We used Robert’s Rules normally but if we had a real fight on our hands…we would take it off the floor. We would put them in a room with a mediator to find out where is the common ground here.”

“I think it’s really important for emerging feminists today to grapple with the diversity of the history of feminism.”

Margaret McPhail

The archives serve to counter assumptions that the second wave of Canada’s women’s movement was homogeneous, or run exclusively by and for white, educated, wealthy women.

“I think it’s really important for emerging feminists today to grapple with the diversity of the history of feminism,” says McPhail, noting that young people are sometimes surprised to learn of the existence of groups like the Congress of Black Women of Canada, the Black Women’s Collective, Women Working with Immigrant Women, or Intercede.

“Finding all that out is exciting. I find it much like my own experience coming to feminism in the late 60s and early 70s and learning a lot about the suffrage movement in England or the U.S. and so on…There was a whole richness to the history of the fight for women’s equality and the way it crossed over into other movements for social change and social justice that was very exciting for me at that time. I imagine today it would be exciting for emerging feminists (to discover these materials). It informs the discussions of today.”

Discovering those materials has been exciting indeed for Julia Aguiar, a Masters student in history at Queen’s University. She has used the Women’s Archives extensively in her research on immigrant women’s organizations and their struggles to have their perspective included in the broader women’s movement from the ‘70s to the ‘90s.

“A lot of these struggles are ongoing,” Aguiar says. “Having this history preserved and documented… shows us there are people who have always been resisting sexism and the power structures. People were always imagining different ways of being. That is something that feminist history has taught me. We don’t have to accept the current conditions we live under.”

Aguiar expresses awe when she thinks of the second-wave feminists; all these people from diverse backgrounds, writing newspapers, marching and organizing everything from grassroots initiatives like the Bookmobile to national events, without the convenience of search engines or social media.

“It totally blows my mind as someone who has had the internet for most of my life,” Aguiar says. “They were so fierce. It’s incredible.”