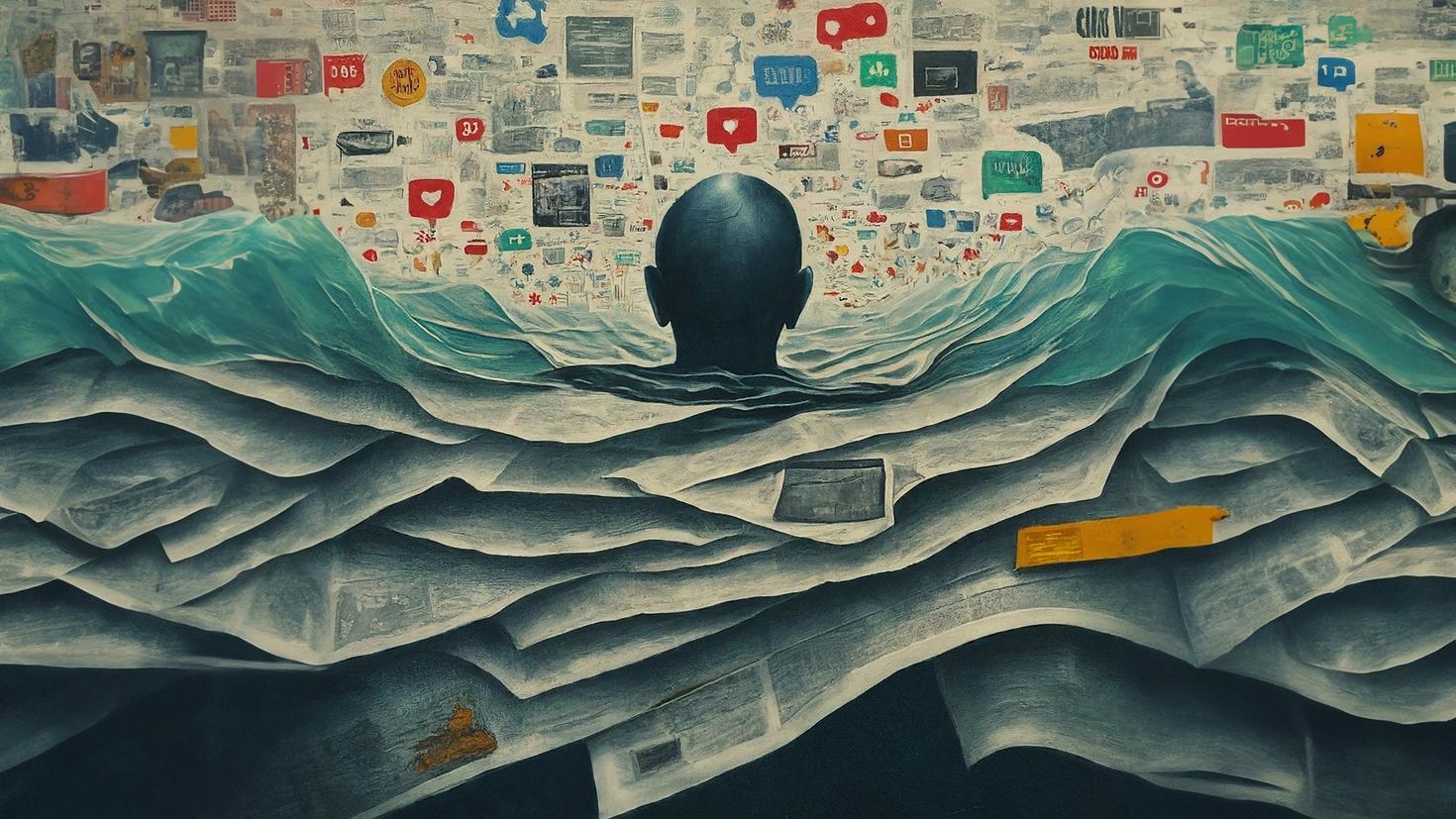

However, global debates, characterized by conflicting opinions, polarizing political messages and conspiracy theories are eroding public confidence in what is true and what is false.

Given this environment, made worse by dubious internet sources and social media algorithms set to push ideologies, we are left to wonder what can be done to combat misinformation and its divisive effects on society? What basic tools does society need to combat misinformation and prevent it from evolving into social and organizational crises?

In May, the University of Ottawa will host the 91st Annual ACFAS Conference, the largest multidisciplinary academic gathering in the Francophonie. Four members of our research community will be conducting symposiums on misinformation and disinformation.

Curious? Read on!

Cultivating critical thinking in society

Mitia Rioux-Beaulne, Faculty of Arts

Professor Rioux-Beaulne’s research looks at the perspectives of 18th-century philosophers who questioned the role of scientific institutions as places for creating, validating and disseminating knowledge.

The two main institutions of the time were the academies — centres where knowledge was decided and communicated to the public, like a university — and the Encyclopédie — a book of knowledge created by and for the public. The Encyclopédie was compiled under the stewardship of the French encyclopedists Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert, who saw knowledge as something that was constantly changing.

“Whether in the academies or in the Encyclopédie, there were internal moderation systems, writing rules and a process to legitimize knowledge,” explains Rioux-Beaulne, who teaches philosophy at the University of Ottawa.

“It wasn’t just a matter of saying, ‘Believe this, and don’t believe that.’ Rather, it was a question of explaining what tools people needed in order to become critical readers themselves.”

In Professor Rioux-Beaulne’s opinion, today’s newspapers and media rarely talk about validation tools and processes when they publish the findings of scientific studies. As a result, the line between science and opinion tends to blur, which often undermines the credibility of certain results. “In my view, it raises major concerns about the harmful impact of that approach on the public discourse.”

Professor Rioux-Beaulne once again points to Diderot when asked about how to reconcile differences of opinion in academia. The philosopher of the Enlightenment brought together a host of widely divergent thinkers to contribute to the Encyclopédie and tasked them with reviewing and criticizing its contents, and to react to each other’s contributions.

According to Professor Rioux-Beaulne, contradictions were seen as contributing to a broader understanding of the information. “The idea was not to create a science that imposed a single discourse, but rather to generate possibilities for healthy debate based on sound scientific principles.”

Professor Rioux-Beaulne also says that philosophers of the time wanted to instill in people the idea that they should take a more critical and deeper look at knowledge, with institutions playing a formative role in shaping critical thinking.

“In more contemporary terms, we can agree that a functional education system is an essential prerequisite for a healthy democracy. Citizens should be able to vote in an enlightened manner. Therefore, failure to invest in our education systems would almost inevitably undermine democracy and create an environment conducive to manipulation, where citizens’ actions and decisions are influenced by a faulty concept of reality.”

Add Professor Rioux-Beaulne’s symposium, Qu’est-ce qu’un héritage philosophique ? la philosophie et son rapport au passé (What is a philosophical heritage? Philosophy and its relationship with the past), to your ACFAS Conference agenda.

Developing the ability to popularize science

Adam Brown and Elaine Beaulieu, Faculty of Science

In 2013, Professor Adam Brown put together the first-ever “how to popularize science” course in a university science program in Canada. It was no small feat, given that up until then, the discipline had been relegated to programs in the humanities.

“In today’s world, scientists need to be able to communicate with the public. It’s more than just communicating data and scientific findings. The goal is for people to become interested in, and engage with, science,” Professor Brown remarked.

For her part, Professor Elaine Beaulieu’s focus is on transforming scientific information into visual images. In her courses, Professor Beaulieu has her students decide what key information needs to be passed on, and then to communicate it visually. “You can reach a wider audience that way.”

Beaulieu, who teaches biology, says that over the past few years, with the pandemic and the increased frequency of major natural events, a new audience for scientific knowledge has emerged, namely the general public.

“From now on, developing skills in this emerging discipline should be considered essential in the training of scientists. This will allow us to be proactive rather than reactive, and to train scientists in these skills before crisis strikes and misinformation spreads.”

Professor Brown says that fighting against misinformation by disseminating facts will fall on deaf ears more or less, since misinformation is rarely based on facts. “It tends to be driven by values or emotions.”

“We need to look at the situation carefully and capitalize on the interdisciplinary nature of popular science, which encompasses a number of non-scientific areas, such as culture, history, economics, politics, international issues, ethics and sociology. It would be a shame not to make the most of them.”

Add Professors Brown and Beaulieu’s symposium, Défier les normes pédagogiques : repenser la formation en vulgarisation scientifique dans l’enseignement supérieur (Challenging pedagogical norms: rethinking popular science training in higher education), to your ACFAS Conference agenda.

Ongoing assessment critical for effective crisis communications

Ivan Ivanov, Faculty of Arts

Ivan Ivanov teaches organizational communications at the Faculty of Arts. Professor Ivanov says that in times of crisis, “there is a dual information process. There’s a lack of information initially, so you amass information by looking to various sources. But, you quickly become submerged in a flood of information.”

That’s when we need to be wary of misinformation, disinformation and rumours. “It’s like a snowball. The most formidable weapon against misinformation is official institutional communication, transparent information and organized crisis management,” adds Professor Ivanov, who is currently researching the evolution of public relations practices in the digital era in the Canadian federal government.

To establish an effective crisis communication strategy that combats misinformation, it is important “to be flexible and to adapt to the environment. The secret is to be in continuous assessment mode. You have to use a combination of communications strategies and be flexible in your approach as the information changes and the crisis evolves. Otherwise, the strategy won’t work.”

And we should not expect things to return to normal, because there really is no such thing as “normal” outside a crisis. Professor Ivanov says that studying crises in stages — pre-crisis, acute phase and post-crisis — no longer makes sense in a world of permanent crises. According to the work of his research team, these stages need to be seen as a continuous, iterative process, rather than fragmented by successive phases.

Professor Ivanov warns against the common belief that the re-evaluation of crisis management strategies is a failure. “On the contrary, it’s a key stage in the process that allows us to improve. You need to analyse the situation constantly and (re)assess the environment as often as necessary.”

“Looking back helps us understand the present and adjust our strategy for the future.”

Add Professor Ivanov’s symposium, Crise! Quelle crise? Faire dialoguer des approches et des pratiques communicationnelles quand la crise devient l’ordinaire (Crisis! What crisis? Bringing together communication approaches and practices when crisis becomes ordinary), to your ACFAS Conference agenda.