Eulachon grease, thick and golden, is not just food — it is medicine, heritage and identity. Traditionally used in cooking, healing ointments and as a nutritional tonic, eulachon grease is often shared among families and gifted across nations. In recent years, as climate shifts and industrial encroachment threaten both species and practice, communities are seeking to protect and validate their knowledge through collaboration with researchers who respect Indigenous data sovereignty.

That’s where the work of Anik Martin, a recent graduate of the University of Ottawa’s master’s program in environmental and chemical toxicology, comes in.

Ancestral knowledge meets molecular science

Martin’s research places the guiding principle of two-eyed seeing at the forefront: viewing the world “through one eye with Indigenous knowledge and the other with Western scientific perspectives, using both together for the benefit of all.” By integrating First Nations’ traditional knowledge of eulachon grease-making with advanced lipid analysis techniques, her project honours community expertise while adding new layers of understanding through molecular science.

Working under the supervision of Professor Laurie Chan, a leading expert in toxicology and environmental health at the Faculty of Science, Martin spent time in Alert Bay with ‘Namgis families who continue the centuries-old practice of rendering eulachon into grease (t̕łi'nagila). Her scientific focus is on lipidomics — a branch of analytical chemistry that examines the composition of fats in biological samples. With support from Rochelle D’mello, a research associate, and Zoran Minic, lab manager and mass spectrometry expert at the John L. Holmes Mass Spectrometry core facility, Martin and Chan analyzed how traditional preparation methods influence the nutritional profile of the grease.

“The idea is to identify and quantify the different fats in the grease using mass spectrometry,” explains Martin. “We want to show the cardiovascular and general health benefits this oil contains — something the communities already know, but now with evidence that might help protect their food practices from future regulation or external interference.”

By applying rigorous scientific methods to cultural knowledge, Martin’s work helps validate and preserve Indigenous foodways and ensures that the knowledge, and the rights tied to it, remain in Indigenous hands.

“Although once central to their traditions, the Nuxalk can no longer produce eulachon grease due to the disappearance of eulachon from their territory.”

Anik Martin

— Recent graduate of uOttawa’s master’s program in environmental and chemical toxicology

A communal and spiritual practice

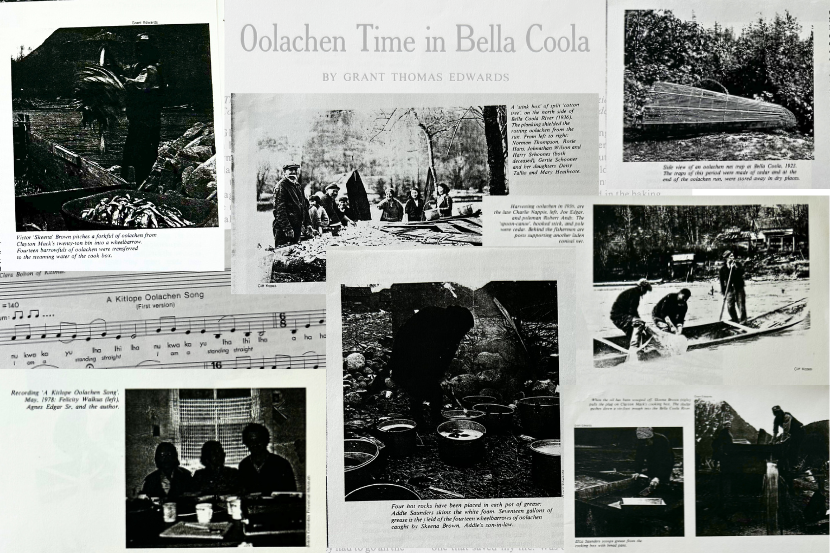

Rendering the grease is a communal affair steeped in ceremony and meticulous practice. Families travel to Dzawadi, the mouth of the Klinaklini River, during the fish run. Once caught, the eulachon are placed in sandy pits to ferment, traditionally for up to 14 days, depending on temperature and family preference. After fermentation, the fish are cooked in large vats of hot water and stirred gently with wooden forks until the precious oil rises to the surface.

This oil is then carefully scooped off, strained, and stored. Every step — from the placement of nets downstream to catch the eulachon to the final straining of the grease — reflects a deep respect for the resource.

“Some call it liquid gold,” says Martin, “and it really is, both in value and meaning. It’s not something people give away easily. You need to build and foster relationships.”

Martin describes her time with the ‘Namgis as transformative. She was invited to participate in a community camping trip (Laxwe’gila, which means ‘strength building’ in Kwakwala) — an intergenerational gathering where elders teach youth about medicine, stories and place. It was there that she met two key community members, Alana Jacobson and Gana Dawson, who became her informal guides, introducing her to families willing to share their grease and stories.

“Grease processing is personal to each family even within the community. Fat rendered from eulachon holds deep cultural, nutritional, social and economic significance for coastal First Nations in BC.”

Anik Martin

— In the Department of Biology at uOttawa, she worked with Professor Laurie Chan

Research rooted in reciprocity

Professor Chan’s collaboration with coastal First Nations began more than 30 years ago, when he was first invited to investigate contaminant risks in eulachon. At the time, he found no traces of mercury or other concerning chemicals — a finding that helped communities affirm the safety of their traditional foods.

Today, thanks to advances in analytical chemistry, the collaboration continues with a broader lens. Using state-of-the-art mass spectrometry tools, researchers can now break down the grease at the molecular level to identify its full lipid profile — a precise map of the fats and nutrients it contains.

With eulachon now considered endangered in many regions, these research partnerships carry added urgency. The fish, and the knowledge tied to it, are not easily replaced. For the communities that still make the grease, the stakes are clear: this isn’t about nostalgia — it’s about survival.

“The goal isn’t just to publish findings,” says Professor Chan. “It’s to support First Nations in asserting control over their health, their food systems and their data. They own the knowledge we help generate.”

By grounding their research in community priorities, Martin hopes this work will contribute not only to science, but also to sovereignty. “Grease tells a story,” she says. “And we have to make sure it’s still being told for generations to come.”