According to Frize, when the dean of the program got wind of her application, he called her father and advised him to talk her out of it. A neighbour, who happened to head up another department at the university, also called Frize’s father to urge him to reign in his ambitious 21-year-old daughter. Engineering, they said, was not for women.

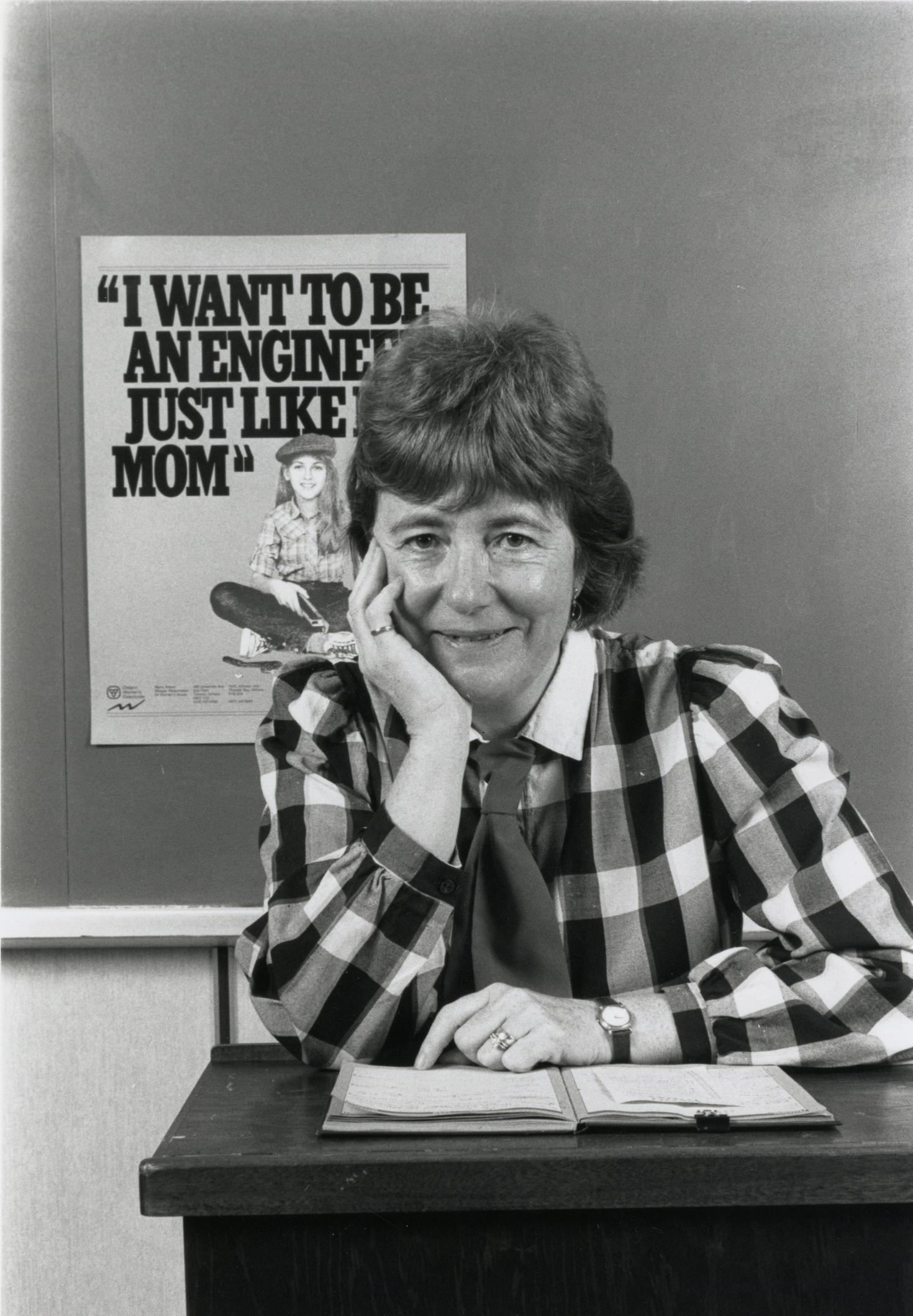

Frize and her father ignored those entreaties. She not only became the first woman to graduate with an engineering degree from uOttawa, she went on to earn two Masters degrees and a PhD at other institutions. She then worked as a clinical engineer for 18 years in the biomedical field, developing a software program to predict complications in premature babies and perfecting a technique to detect arthritis using infrared cameras. In 1989, Frize was named to the newly created position of National Nortel-NSERC Chair for Women in Engineering at the University of New Brunswick.

Frize is one of hundreds of pioneers whose official documents, personal papers, minutes, and memorabilia are housed in uOttawa’s Women’s Archives; bold women who thrived in male-dominated fields during the second half of the last century. Their stories can provide inspiration and encouragement to anyone struggling to get ahead in STEM.

Frize is a big believer in the power and importance of remembering and disseminating the stories of inspirational women in traditionally male-dominated fields. She writes the following in the preface to her memoir:

“Whenever I felt discouraged, or felt disregarded by my male colleagues, I would turn to the life stories of the female academics and scientists who had forged ahead despite difficult and sometimes hostile working environments.”

Here are some career tips from a few of those women, gleaned from interviews, panel discussions, memoirs, and research into the Women’s Archives, beginning with a few from Frize herself:

- Tip #1: Set meaningful goals

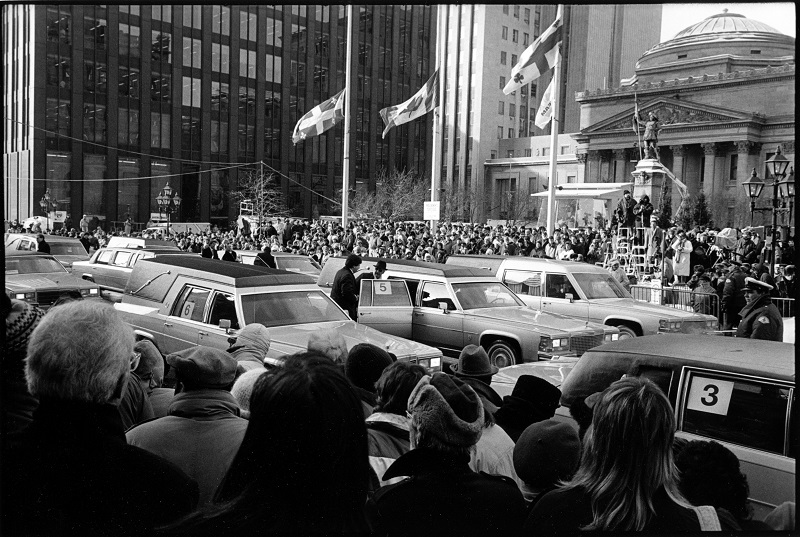

In December of 1989, on what was to be her first day on the job as Chair of Women in Engineering, Frize was called upon to attend the funerals of 14 young women murdered by a deranged, anti-feminist gunman at École Polytechnique, Université de Montreal’s engineering school.

As she left Notre Dame Basilica after the funeral that day, Frize told two colleagues that she had a new goal: to work to ensure that, within the next decade, there would be one thousand more women engineers in Canada for each woman who had been murdered in Montreal.

“…work to ensure that, within the next decade, there would be one thousand more women engineers in Canada for each woman who had been murdered in Montreal.”

Monique Frize

“Actually, there were 15,000 (more female engineers in Canada) ten years later,” says Frize, who has devoted most of her adult life to encouraging girls and women to pursue careers in engineering. She is founder and president of the International Network of Women Engineers and Scientists and has written several books about female scientists and engineers.

- Tip #2: Choose your life partner wisely

This may sound old-fashioned, but it is nonetheless advice that Monique Frize has always given to her students. She maintains that it is crucial for anyone who wants to make a name for themselves in the STEM fields, and also wants children, to choose a supportive partner.

Her first husband, engineer Philippe Arvisais, was the one who inspired her to major in electrical engineering. Tragically, he died in a car accident just weeks before she began her studies. She found love again, and in 1968, married Peter Frize. He was a man of many talents, who encouraged her to focus on her career and did his fair share in raising their son, Patrick.

“My husband did 50 per cent of the parenting and 50 per cent of the housework,” says Frize. “He was a chef. We had a farm for a while in St. Jean near Joliette where we had greenhouses. He did all kinds of things. At one point he bought a pastry shop […] He was unusual, which is one of the reasons I married him. I knew he was the right person; someone who would love me for who I was: a career person who was going to work all my life.”

- Tip #3: Expect a backlash

Frize said she was not particularly persecuted by her male classmates during her undergraduate days. There was one “nasty” young man, she said, who teased her about being a widow, but the others were mainly supportive. She said her impression is that things changed gradually in ensuing decades for female engineering students.

“When there is only one woman, you are a token. You’re like a mascot. You’re not threatening,” she said. But in the late 80s and early 90s, as the proportion of women enrolled in engineering programs approached 15 per cent, a backlash started. She actually heard the phrase “women are taking over” in her engineering circles at that point.

- Tip #4: Build a network and tend to it diligently

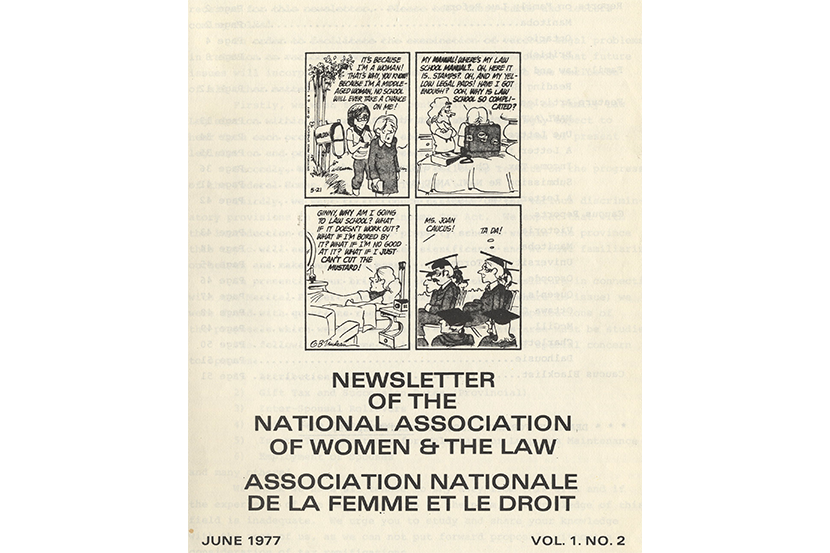

The late Shirley E. Greenberg was a lawyer and philanthropist whose contribution to feminist causes in the Ottawa area were considerable. She wrote extensively on legal issues affecting women, and she co-founded Ottawa’s first all-female law firm in 1978. She helped found the Ottawa Women’s Centre, The Women’s Career Counselling Centre, and Interval House – a shelter for women suffering intimate partner violence.

But friends say her greatest talent was networking; bringing feminists together socially and then inspiring them to take concrete action.

“Shirley hosted, she organized, she volunteered to pull women together to talk about important issues, and activism and plans and strategies,” says Constance Backhouse, a professor at uOttawa’s Faculty of Law and long-time friend to Greenberg. “That was a role she continued to play until the very, very end.”

Backhouse got wind of Greenberg’s all-female law firm when the former was teaching law at the University of Western Ontario in London, early in her career.

“Shirley’s reputation had spread across the province, if not wider,” says Backhouse. “She was one of the first of very few women to define her new law practise as a feminist law practise. I had a growing number of law graduates, feminists who were graduating and looking for a way to have their career based in feminist principles. At the time, it was hard to know where to send them, because they had to article for a year before setting up practice. So, there was kind of pipeline that went from my class” to Shirley’s firm.

Later, Backhouse met Greenberg when the former was asked to speak about sexual harassment at a City of Ottawa event. Whenever a feminist speaker came to town, Greenberg could be counted on to organize a gathering at her home to prolong the networking opportunities.

“She just had gatherings of women and […] those gatherings were absolutely necessary and essential. They were the springboard to much of what we accomplished,” says Backhouse. “People talk a lot about her philanthropy and she and a few others were absolutely ground-breaking in terms of understanding [the importance of] philanthropy as directed towards feminist work. That was very unusual.”

But Backhouse says it was Greenberg’s ability to “create a space, a gathering, a welcoming place” that set her apart. “She was at the pivotal inside of so many of those grassroots feminist groups across Ottawa. She was just the heart, the heartbeat of Ottawa feminism.”

- Tip #5: Be wary of overt sexism; but be more wary of subtle sexism

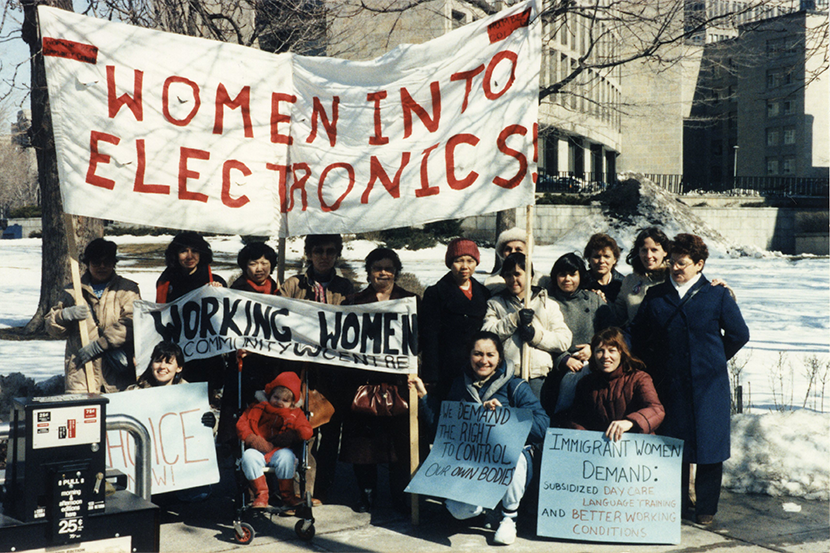

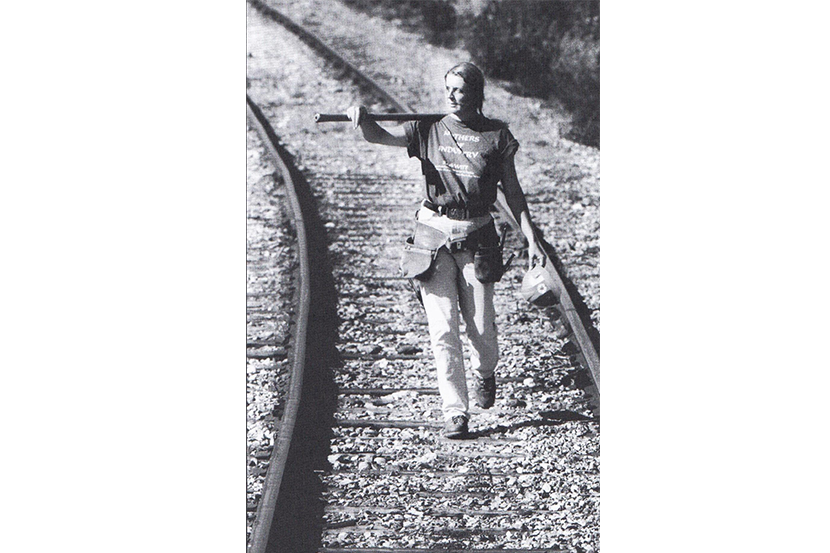

Valerie Overend is a skilled carpenter and a long-time advocate for women in the trades. She co-founded the Women’s Work Training Program in her hometown of Regina in 1995. A Red Seal Carpenter, she has represented Saskatchewan as a Director of the Canadian Vocational Association, and has also served on the Board of Directors of the Canadian Apprenticeship Forum and the National Women’s Reference Group on Labour Market Initiatives, a network of women and women’s organizations focussed on labour market issues.

Overend says she has encountered many forms of sexism over her lifetime, first as a student of oceanography and lab technician at a biological station in Nanaimo during the summers, and then as she transitioned into her career as a carpenter. She decided to apprentice in carpentry at the end of the 1980s, when she became a single mother and needed a solid career.

“My husband had left me and I had to feed my kids,” she told an online panel on Women in STEM organized by the uOttawa Library last spring. “It was so simple. I did a list of my skills and abilities.”

She was good at math, had always enjoyed working with her hands, loved creative pursuits, and working outdoors. So carpentry seemed a particularly good fit, and since she had already been dabbling in it–carving and making simple furniture– she figured she would find it satisfying as a career.

Overend went on to earn her certification as a Red Seal Carpenter, co-founded the Women’s Work Training Program in Regina in 1995, and has devoted much time and energy to encouraging girls and women to consider careers in the trades. She had been the only woman in her certification program in the province at the time, and it was not easy.

But Overend says the blatant sexism she encountered on construction sites was actually easier to handle than the more subtle forms she had encountered at university and at the biological station.

“They were both very sexist environments […] I’m pretty sure they still are,” Overend said. “I found it much more difficult to handle myself with scientists than with construction workers. People are generally surprised to hear me say that. But the old guys at the biological station and at the universities, they just wanted you to stay in your own lane. They didn’t want me there. They wanted me to clean up after them, do some recording, do some collection, fine, take some notes. But I didn’t find they were very good at sharing information with me. It felt like they were being really protective about what they knew, and that if I knew it, then it might somehow diminish what they knew and I just really had trouble with that.

“When I started working construction, I thought it would be ten times worse. It wasn’t really, because they were just really transparent. They just said, ‘Well we don’t think you should be here.’ So, there were no secrets, there was no undermining and subterfuge. It was just very apparent. ‘You shouldn’t be here. What are you doing taking our jobs?’ It took me a while to realize that I could just tell them off. You can’t do that in a university,” especially as a young woman just starting out, Overend said.

Being bold enough to call the men out when they were out of line was effective, she said. “They actually respected me more when I did that.”

- Tips #6, #7 and #8: Be resilient; Be brave; Be bold

Claire Deschênes remembers vividly her first day of class in mechanical engineering at Université de Laval in Quebec City.

“I was surprised on the first day of mechanical engineering to be the only woman in the room. I will never forget it. Everybody stared at me, the professor, and the students, and I went instantly red. I spotted a chair and I went to sit down, and I thought, ‘My gosh, what am I doing here? Why did I choose this?’”

But by this time, the young Deschênes had already learned to manage some difficult situations. Her mother had been diagnosed with severe multiple sclerosis when Deschênes was just 14 and her father became seriously ill soon after. He died when she was 17.

“I became like a mother for my sister and brother. And this situation showed me that life is unpredictable and could be difficult sometimes. I developed the idea that I should go with my strengths and have a career that would help me for a long time in life.”

The first year was very difficult and Deschênes failed her first exam. “I thought, ‘Gosh I’m not in my place at all!’ But after a while, things started to improve. I was not so bad a school. I made friends with my colleagues and their girlfriends. I felt so surrounded by men that I forced them to bring their girlfriends to all the parties we had.”

Deschênes went on to become the first female professor of engineering at Université de Laval in 1989. She founded the Hydraulic Machine Laboratory (LAMH), held the NSERC Chair for Women in Science and Engineering from 1997 to 2005. She was a founding member of the International Network of Women Engineers and Scientists – Educational Research Institute (now the Canadian Institute for Women in Engineering and Sciences), a Fellow of Engineers Canada, and a Member of the Order of Canada.

“It takes resilience,” she told the STEM panel in Spring 2022. “When I started in the laboratory, it was not obvious that I would make a career doing that because I was sort of invisible. There was competition with other laboratories, and they (dismissed her as) ‘the little Deschênes’. I had to be very resilient. And after a while the industries understood that I had something to bring.

“So resilience is very important,” says Deschênes. “Be brave…Be bold. Go on with what you want to do.”

“Be brave…Be bold. Go on with what you want to do.”

Claire Deschênes