The Cameroonian coast was explored in 1471 by the navigator and explorer Fernando Póo, who was responsible for naming the Rio dos Camarões (‘River of Shrimps’) which became Cameroun (French), Cameroon (English) and Kamerun (German). Europeans began trading with the local populations, starting with the Dutch and followed by the British and the Germans.

Cameroon

English-French bilingualism

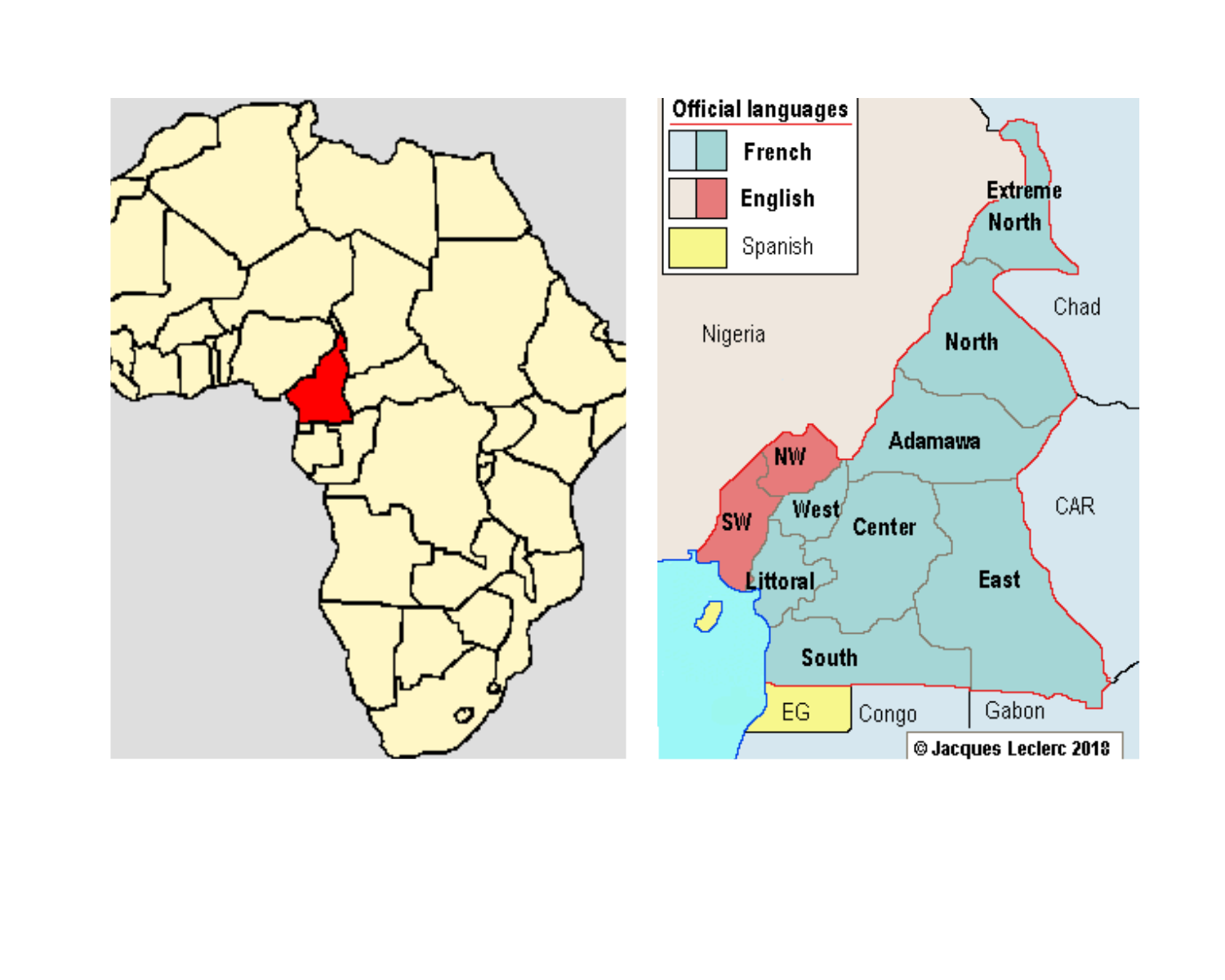

Cameroon is not a federation like Canada. Rather it is unitary state divided into 10 administrative regions (Art. 61 of the Constitution) which possess very few powers. The regions are the Extreme North, the North, Adamawa, the Northwest, the Southwest, the West, the Littoral (Douala), the Centre (Yaoundé), the East and the South. Like Canada, Cameroon has two official languages, English and French, but unlike Canada with its eight Anglophone provinces, one Francophone province (Quebec) and one bilingual province (New Brunswick), in Cameroon there are eight “French” regions and two “English” regions. The two English regions are the Northwest and Southwest. All ten “regions” were called “provinces” before Decree No. 2008/376 of 12 November 2008, and in documents that are not up to date the term “province” rather than “region” can still be found.

A look at a geographical map of Africa shows that Cameroon is located on the border between the English zone of influence (Nigeria) and the French zone (Chad, the Central African Republic, Gabon, Congo). The only exception is Equatorial Guinea, which has Spanish as its official language although since 1998 French has become the “second official language”. The word “second” reflects the power relationship between Spanish, the predominant language, and the almost symbolic importance of French. Portuguese became the “third official language” in Equatorial Guinea in 2011.

A brief history of Cameroon

German Kamerun

The Germans occupied almost all of their Kamerun from 1884 to 1916. German-speaking missionaries from the Societas Apostolus Catholici (‘Society of the Catholic Apostolate’ ) settled in the German colony in 1890 and offered education in German to those who wanted it, while at the same time opening village schools where local languages — Duala, Bakweri, Ewondo, and Nguma, etc.—were used. The German language exerted an attraction on members of urban Cameroonian society, who wanted to be able to communicate with the colonial power.

In 1891, the German governor Eugen von Zimmerer attempted to impose Germanization policy on Kamerun in order to provide the administration with local managers who could speak German. Despite pressures exerted by the German colonial authorities, the missionaries continued to use local languages in their Christian evangelization. However, the First World War placed German Kamerun between two other major powers in the region, France and Great Britain.

British Cameroon

In 1916 German troops abandoned Kamerun to their two greatest rivals, France and Great Britain, and the Treaty of Versailles (1919) contained a provision for the two to share the former Kamerun. In practice, French Cameroon, comprising four fifths of the territory, was administered as a French colony, and British (or Western) Cameroon — one fifth of the territory — was integrated into Nigeria as an English colony. Each of the colonizers would mark “its” Cameroon with its linguistic fingerprint by imposing either English or French on its colony.

The British colonial administration, which wanted to minimize investment costs in its colonies, was content to incorporate its “piece of Cameroon” into the neighbouring colony of Nigeria, which resulted in the creation of “a colony within a colony”. As a result, British Cameroon was delayed in both its social and economic development. Understandably, Anglophone Cameroonians in the British colony couldn’t help but notice the considerable gap between the development in their colony and the situation in French Cameroon.

The establishment of borders and the federation

In 1961, the independence of French Cameroon led to the question of borders with British Cameroon, borders which had never been established between the two colonies. There was a territorial vagueness between the regions that are now part of Nigeria (Northern Cameroon) or part of Cameroon (Southern Cameroon). For this reason the United Nations conducted a referendum in which the two populations concerned had to choose which country they wanted to join, the Federation of Nigeria or the Republic of Cameroon. The latter would then become a federation of one English and one French state.

In the referendum held on 11 February 1961, the residents of Southern Cameroon voted massively to separate from Nigeria and join the Republic of Cameroon, while in Northern Cameroon a majority voted in favour of joining Nigeria. This is how the so-called “English” population of Southern Cameroon under British administration found itself in a predominantly French-speaking country.

On 1 October 1961 Cameroon became a federal republic composed of two states: English-speaking Cameroon (the current Southwest and Northwest regions) and French-speaking Cameroon. The Federal Republic of Cameroon (1961-1972) consisted of four assemblies, one Federal Assembly and one in each of the two federated states, as well as an assembly of traditional chiefs. There were thus three governments, one in each federated state and one federal government. The residents of Southern Cameroon voted to become Cameroonians rather than Nigerians because they had been promised an autonomous English-speaking state within the binational state.

At the time of independence in 1961, the Cameroonian languages were so numerous (between 260 and 300) and so diverse (consisting of languages from the Niger-Congo, Nilo-Saharan, Bantu and Afro-Asiatic families, some with very few speakers), that it seemed more practical to have French and English as the official languages of the nation. In any event, at that time no one was interested in the fate of national languages, very few of which had a written form. Although French and English were the official languages of Cameroon, generally speaking the national languages continued to be very much alive, although marginalized from a social point of view.

The abolition of federalism (1972)

After a referendum in May 1972 Cameroonian federalism was abolished and the two federal states disappeared, replaced by a single centralized state divided into ten administrative provinces (now called “regions”) of which two were English and eight French. Understandably the Anglophones in the English provinces felt that their rights had been betrayed because they had chosen Cameroon rather than Nigeria due to federalism and the division of powers and languages by territory. This constitutional change was adopted by a simple majority; it also heralded a marginalization of Anglophones due to more centralized power in Cameroon.

More than five decades after independence, the unification of Cameroon in 1972 is being challenged and called into question by the Southern Cameroon National Council (SCNC), an Anglophone political party that campaigns for the secession of the two Anglophone regions and the creation of an independent state which would be called “Ambazonia”. In 2018, secessionist groups increased their violent actions against symbols of the state. For its part, the African press is concerned that an experienced guerilla organization seems to be taking up residence in the Anglophone regions of northwest and southwest Cameroon. The press has also criticized the Cameroonian authorities for having made the decision to call in the army rather than engaging in talks with the Anglophone secessionists. On one hand, the armed rebel movements are in a power struggle with Yaoundé; on the other hand the government does not want to negotiate with those it considers “terrorists”. However, this "Anglophone crisis" is the result of bad governance by the Cameroonian state, and the Anglophone minority finds itself caught between two fires, or in the words of Amnesty International “: "People are caught in the crossfire between the hammer and the anvil.”