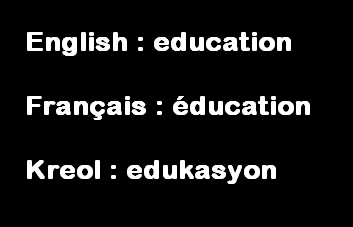

To understand the dynamic of languages in Mauritius, it must be taken into consideration that, setting aside the fact that that only a small number of the population speak French as their mother tongue and even less speak English, the government for its part tends to prefer English monolingualism, whereas the Creole population feel a greater affinity with French than English. For the Mauritian government, English is the first official language, and French the second; and Creole simply does not exist at all – legally speaking. To make a light-hearted reading of the status of languages in Mauritius: English is the official language, French might be the “officially official” language but non-official Creole is the most important. In brief, the population is ‘Creolo-phone’ and Francophile; the government is anglophone and anglophile, but social prestige remains the domain of French. We therefore witness three languages in cooccurrence: English, French and Creole. As for the Oriental languages deemed ‘heritage languages’ (Hindi, Tamil, Marathi, Chinese, etc.), these are only employed in specific personal situations.

The official language of the Assembly

When reading the Constitution, it is clear that English is the only language of the National Assembly, since it is the language of debate and of written law. Article 49 of the 1968 Constitution also deals with languages authorized in the National Assembly:

Section 49 (Original version) Official language

The official language of the Assembly shall be English but any member may address the chair in French. Section 33 Qualifications for membership

Subject to section 34, a person shall be qualified to be elected as a member of the Assembly if, and shall not be so qualified unless, he – (d) is able to speak and, unless incapacitated by blindness or other physical cause, to read the English language with a degree of proficiency sufficient to enable him to take an active part in the proceedings of the Assembly. | Article 49 (Traduction non officielle) Langue officielleLa langue officielle de l'Assemblée doit être l'anglais, mais un membre peut s'adresser à la présidence en français. Article 33 Qualités requises des membres Sous réserve des dispositions de l'article 34, une personne n'est admissible comme membre de l'Assemblée que si elle satisfait aux conditions suivantes: [...] (d) être capable de parler et – à moins qu'elle en soit incapable pour cause de cécité ou pour toute autre cause physique – de lire l'anglais avec un degré de compétence suffisant pour lui permettre de prendre une part active aux délibérations de l'Assemblée. |

According to Constitutional prevision, English is obligatory in the Assembly, while the use of French is authorised: a way of saying that it is not prohibited, but tolerated. As for Mauritian Creole, it is glossed over, and from a legal point of view, it is silently prohibited. The National Assembly has never modified Article 49, and it well illustrates the character of the official discourse concerning English, and the practices surrounding French in reality in Mauritian society.

Elsewhere, the facts seem to contradict this policy statement concerning English, French and Creole. All laws adopted before 1814 are entirely in French, including contemporary modifications, but laws adopted since 1814 are only written in English. Parliamentary debates clearly take place in English, but also in Creole and French. Members of the Assembly – all Creole speakers – discuss laws in English and more rarely in French, but always express themselves in Creole when exchanges become informal or aggravated: Creole is the language of insults, of invective, of pleasantries, etc. As for the Indo-Mauritian members, they express themselves almost exclusively in English, even if they know Creole. Thus, English, French and Creole are all used in Parliament, but English is employed more often than French and Creole together, with the latter employed less often than French.

In numerous cases, many politicians alternate two – sometimes all three – languages when they speak, often in a single phrase. However, words spoken in Creole are not transcribed in Hansard, the official journal of record, which can often render certain published messages slightly incoherent, when statements ought to appear in English, French and Creole together because they were spoken as such; yet only speeches in English and French appear in the official record. No simultaneous translation service exists in the Mauritian parliament. Simply speaking, it could be said that English is the official written language, and French and Creole are the official spoken languages.

All in all, in the domain of legislation, English necessarily finds itself a step ahead of other languages. We find an unequal bilingualism, balanced in English’s favour. Language practices in the Federal Government of Canada differ completely: firstly because members of parliament benefit from simultaneous translation in both languages, and secondly because the writing and enactment of laws takes place in both French and English. In Mauritius, only English is employed in the writing and enactment of laws.

The Mauritian government and public administration publish all their official communications in English, and legal notices in local newspapers, whether they be in French or English; though these same communications are translated into French for the radio.

Languages and justice

As a great number of languages exist within the republic of Mauritius, one might expect that a certain number of these would be admissible in court. In fact, article 131 of the 1945 Courts Act, which is still in force, states that the language used in front of an intermediate court is English, but it is possible to address the court in French. It represents the same paradox: English is always the first official language, but this fact doesn’t exclude other languages. In addition, when a witness convinces a court that he doesn’t possess sufficient competence in English or French, he can testify in “the language which he knows best”, which permits Creole in principle, and possibly heritage or Oriental languages:

Courts Act (Original version) Section 131 Language to be used 1) The language to be used in the Intermediate Court or in any District Court shall be English, but any person may address the Court in French. 2) Where any person who is required to give evidence, satisfies the Court that he does not possess a competent knowledge of English or French, he may give his evidence in the language with which he is best acquainted. 3) Where any person gives evidence in a language other than English or French, the proceedings shall, if the Court so directs, be translated. Section 132. Interpreters Any person appointed to act as interpreter at the Intermediate Court or any District Court may, in addition to his duties as interpreter, be assigned such other duties as the Magistrate having the supervision of the Court may determine. | Loi sur les tribunaux (Traduction non officielle) Article 131 Langue utilisée

1) La langue utilisée devant la cour intermédiaire ou devant les cours de district doit être l’anglais, mais il est possible de s’adresser à la cour en français. 2) Lorsqu'un témoin convainc la cour qu'il ne possède pas une connaissance qualifiée de l'anglais ou du français, il peut témoigner dans la langue qu'il connaît le mieux. 3) Lorsqu’une personne témoigne dans une autre langue autre que l’anglais ou le français, les témoignages doivent être traduits si la cour l’ordonne.

Article 132 Interprètes Quiconque est désigné comme interprète par le tribunal intermédiaire ou un tribunal de district peut, en plus de ses fonctions d'interprète, se voir confier d'autres tâches que peut décider le magistrat chargé de la présidence du tribunal. |

Article 41 of the Courts Act states that “the official language to be used in front of the Supreme Court of Mauritius must be English”, but if a litigant appears before the court and convinces them that he doesn’t have knowledge of English, “he can testify or make a declaration in the language he knows best”. This type of arrangement reflects Mauritian politics well: the language of the state is English, but French is authorized, as well as the language which one “knows best” and which, though not named, means Mauritian Creole. According to Article 175 of the Courts Act, testimonies made in languages other than English or French must be translated, subject to the provisions of Article 176 and 178. These articles exclude testimonies of civil and criminal nature.

It must be understood that the Civil Code (1808), which still carries the name of the Napoleonic Code, and the Code of Civil Procedure (1808) are of French origin and were written in French, and later translated into English, although only a few of the articles of the codes remain applicable, and not a single article relating to language exists within them. Let us remember that in Canada, the Canadian Criminal Code (which originated from Common Law) makes provision for French and English, while the relevant Civil Code of each of the provinces doesn’t necessarily make such a provision; just as in Mauritius, the Code civil of Quebec is of Napoleonic inspiration.

It is surprising to note that, while the law allows Mauritians to express themselves in English, French and Creole in court, in practice French remains the most widely used language, ahead even of Creole, which is more frequent than English. Judges tend to pronounce their sentences in French, less often in English and rarely in Creole. However, the language of justice is English!

Language use in public administration

The official language of public administration is English, although this has never been formally inscribed in law. However, the Local Administration Act 2003 states that a local authority councilor should obligatorily be capable of speaking in English and French, with sufficient proficiency to allow them to take an active role in council business.

Local Government Act 2003 (Original version) Section 12.

Qualifications for councillors

Subject to section 13, no person shall be qualified to be elected as a councillor of a local authority unless - (a) he is qualified to be registered as an elector for the election of councillors for any ward of the relevant local authority; and

(b) he is able to speak and, unless incapacitated by blindness or other physical cause, to read English and French languages with a degree of proficiency sufficient to enable him to take an active part in the proceedings of the Council. | Loi sur l'administration locale (Traduction non officielle) Article 12

Qualifications des conseillers

Sous réserve de l'article 13, nul ne peut être qualifié pour être élu conseiller d'une autorité locale, sauf : (a) s'il est qualifié pour être inscrit comme électeur lors de l'élection des conseillers pour un service de l'autorité locale concernée, et;

(b) s'il est capable de parler et, à moins d'incapacité due à la cécité ou d'autres causes physiques, de lire en anglais et en français avec un degré de maîtrise suffisant pour lui permettre de prendre une part active aux travaux du conseil. |

This law bears witness to the fact that English and French are necessary to participate in public administration. In practice, Mauritian officials use French or Creole as their language of work. When they address their fellow citizens aloud, they do so first in Creole, then in French, and then they resort to English if the matter concerns Indo-Mauritians or Sino-Mauritians, or perhaps foreigners or anglophone tourists. In municipalities and villages, in hospitals and healthcare facilities, Creole and French are always used, but English is used when it is necessary. In general, spontaneous usage is of Creole, followed by French. English is reserved for formal requests or for use with citizens of Indian or Chinese origin, or with foreigners. Finally, the majority of Mauritians also speak Creole and French, but read and write in English. Rather than describing an unequal bilingualism, we might talk of a diglossia or triglossia, where languages are divided into specific functions, without impinging on one another.

It remains the fact that the most part of official government documents are written only in English, a practice inherited from British colonialism, which has never been re-examined. As a consequence, all political and administrative functions and posts bear official English titles: Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, President, Vice-President, Speaker, Deputy Speaker, Attorney General, Leader of the Opposition, Junior Minister, Minister Mentor, Minister of Education and Human Resources, Minister of Tourism, Senior Chief Executive, Energy and Public Utilities, Social Security, Prime Minister's Office, Land Transport Division, Public Service Commission, Chief Commissioner's Office, etc.. The President of the Assembly is also called “Speaker” in Mauritian French and not “Président”.

These English titles are evidently translated into French in newspapers, on the radio and on television, in public spaces, in private conversations, etc., but these are never official translations. While it is relatively straightforward to translate ‘Prime Minister’ as premier ministre, ‘Leader of the Opposition’ as chef de l'opposition or ‘Public Service Commission’ as commission de la fonction publique, it is much more difficult to translate Senior Chief Executive which could be translated into French as chef exécutif senior (directeur général) or ‘Energy and Public Utilities’ which could be translated as Énergie et utilités publiques instead of Énergie et services publics.

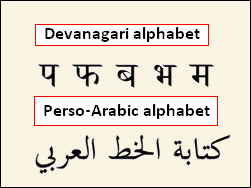

The official currency of the country is the Mauritian rupee, which carries writing in English: Bank of Mauritius, Twenty Five and RUPEES). If there is no French or Creole writing (for example, Roupie mauricienne or Roupi morisien), the currency contains Tamil (மொரீசியஸ் ரூபாய) and Hindi (मॉरीशस रुपय), both of which signify ‘Mauritian rupee’. This follows a tradition practiced in the British Indies and passed on to Mauritius to publish paper money in three languages, in the order English-Tamil-Hindi. Although the Tamils are far fewer in number that Hindi speakers in Mauritius, they base their “right to priority” on the fact that they arrived on the island before members of the Hindu community from the north of India. Before the introduction of the Mauritian rupee, the currency of Mauritius was the ‘Indian rupee’ which was chosen by the British due to the massive influx of Indian rupees following Indian immigration to Mauritius.

In terms of toponymy, the great majority of place names are of French origin: Savane, Pamplemousses, Rivière-du-Rampart, Port-Louis, Grand-Port, Poudre d'Or, Riche-en-Eau, Flic-en-Flac, Nouvelle-France, Grand-Bassin, Quatre-Bornes, La Roche-qui-Pleure, Curepipe, etc. In certain cases, these had been in the past translated from the French by the British administration: Black River, The Mount, Royal Palm, etc. It is this practice which can explain the occasional presence of bilingual place name inscriptions in Mauritius. On Rodrigues Island, it can also be said that toponymy is wholly of French origin: Baie-Topaze, La Fouche-Corail, Plaine-Corail, Montagne-Goyaves, île aux Crabes, île Frégate, île Souris, etc, not to mention other place names such as Anse-aux-Anglais, Baie-du-Nord, Petite-Butte, rivière Banane or caverne Patate.

However, across the whole country, road signage is only found in English, illustrating one of the many linguistic contradictions in Mauritius.

Ultimately, the Creole language, spoken by 86.5% of the population suffers admittedly from a lack of institutional recognition, which creates great frustration among the Creole-speaking population. Administrative practices regarding language use mainly serve to highlight the colonial traditions which favoured English. However, even today, when the political and administrative situation is different and no British officials remain, old habits have remained fixed by conservatism, without being much questioned.