On September 3, 1755, Lieutenant-Colonel John Winslow summoned the Acadians of Grand-Pré together and made the following proclamation at Saint-Charles-des-Mines church in Grand-Pré:

Gentlemen:

I have received from his Excellency, Governor Lawrence, the King's instructions, which I have in my hands. By his orders you are called together to hear His Majesty's final resolution concerning the French inhabitants of this Province of Nova Scotia, who for more than a half century have had more indulgence granted them than any of his subjects in any part of his dominions. What use you have made of it, you yourselves best know.

The duty I am now upon, though necessary, is very disagreeable to my natural make and temper, as I know it must be grievous to you, who are of the same species.

But it is not my business to dwell on the orders I have received, but to obey them and, therefore, without hesitation, I shall deliver to you His Majesty's instructions and commands, which are...

That your lands and tenements and cattle and livestock of all kinds are forfeited to the crown, with all your effects, except money and household goods, and that you yourselves are to be removed form this Province.

The preemptory orders of His Majesty are, that all the French inhabitants of these Districts be removed, and through His Majesty's goodness, I am directed to allow you your money and as many of your household goods as you can take without overloading the vessels you go in. I shall do everything in my power that all these goods are secured to you and that you be not molested in carrying them away, and also that whole families shall go in the same vessel; so that this removal, which I am sensible must give you a great deal of trouble, may be made as easy as His Majesty's service will admit; and I hope that in whatever part of the world your lot may fall, you may be faithful subjects, and a peaceable and happy people.

I must also inform you, that it is his Majesty's pleasure that you remain in the security under inspection and direction of the troops that I have the honor to command.

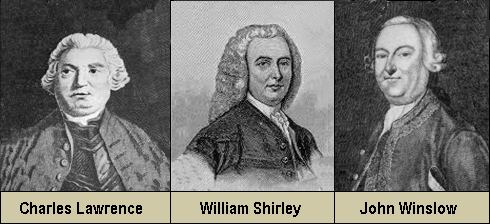

The deportation, which the Acadians would call the "Great Upheaval," was carried out surprisingly fast. Not only did Charles Lawrence put his entire British army of 315 men on the job, he also obtained the support of Massachusetts governor William Shirley to convince the General Court of the Colony to send 2,000 volunteers to drive the Acadians and French out of Nova Scotia. He then brought in a fleet of 16 trading ships requisitioned from New England and expelled the Acadian population, village by village, out of Grand-Pré, Les Mines, Beaubassin, the French Bay area (Bay of Fundy), and others.

Before the end of 1755, more than 7,000 Acadians had been sent into exile. Thousands of others would follow in the years ahead. Out of a population of some 13,500 Acadians, an estimated 12,600 plus were deported, but over 4,000 of them died from infectious disease. Others reached Canada or what remained of French Acadia (the Gaspé Peninsula, Cape Breton, and Prince Edward Island). As illustrated in the table below, the majority of deported Acadians went to France (3,500), followed by Canada (2,000), Massachusetts (1,043), and Connecticut (666).

|

Place

|

Population

|

|

Connecticut

|

666

|

|

New York

|

249

|

|

Maryland

|

810

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

383

|

|

South Carolina

|

280

|

|

Georgia

|

185

|

|

Massachusetts

|

1,043

|

|

Saint John River

|

86

|

|

Prince Edward Island

|

300

|

|

Chaleur Bay

|

700

|

|

Nova Scotia

|

1,249

|

|

St. Lawrence Valley (Canada)

|

2,000

|

|

England

|

866

|

|

France

|

3,500

|

|

Louisiana

|

300

|

|

TOTAL

|

12,617

|

Source: R.A. LEBLANC. "Les migrations acadiennes," Cahiers de géographie du Québec, Vol. 23, No. 58, April 1979, p. 99–124.

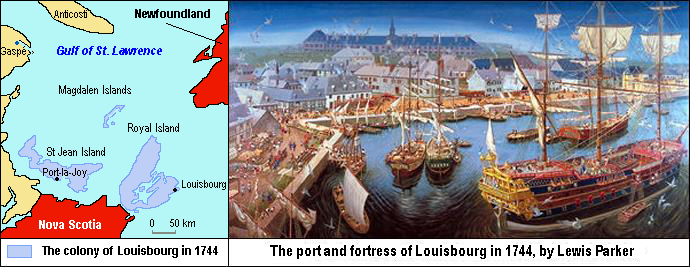

The banishment took until 1762 to complete. The British believed that once the Acadians were dispersed across the colonies, they would no longer pose a risk and would assimilate into the local population. Today, this type of operation would be considered "ethnic cleansing." It was a radical move from a linguistic standpoint, because once the speakers were gone, so was their language! The French and British tried the same thing repeatedly in the small archipelago of Saint Pierre and Miquelon. Between 1690 and 1814, the archipelago changed hands nine times. Four times in 125 years, the settlements were completely levelled and all the colonists deported, the houses destroyed, and fields burned. The difference with the Acadian deportation was that it was conducted on a much broader scale and without authorization from the British government, which gave its approval after the fact. Earlier, in 1745, the English had deported the entire French colony of Louisbourg (4,000 people) to France after it surrendered, but the French returned in 1748.

After that, the heart of Acadia shifted westward, then toward Louisiana, which had become Spanish territory in 1762. During these years, colonial New England complained to London about the arrival of thousands of poor Acadians—French speakers no less—whom the American colonists had to house and feed with no compensation from the British government. London even launched an inquiry to clarify the circumstances surrounding the deportation, because Charles Lawrence had been accused of taking rations confiscated in the name of the king and selling them to the army, and manipulating the distribution of land to the new colonists in Nova Scotia to his own personal gain. But the accusations did not make it into court before Lawrence died in 1760. Overall, the deportation was a radical measure that changed the balance of power between populations. The void left by the Acadians would be quickly filled by English-speaking colonists.