The British quickly installed their generals James Murray, Ralph Burton, and Thomas Gage in the governments of Québec, Trois-Rivières and Montréal, respectively. During the ongoing military occupation of Canada, English general Jeffrey Amherst, successor to Wolfe, proceeded to organize a provisional administrative system; for as long as the Seven Years War continued in Europe, the fate of North America remained uncertain. Nevertheless, some 2,500 French soldiers and administrators immediately left the colony and returned to France; the following year, about a thousand other people anxious about the situation did the same.

British North America

Prelude to the Military Rule of 1760

In 1761, the demographic situation was as follows: Canada's white population was 70,000 inhabitants (and more than 200,000 indigenous people), compared to 1.6 million in New England. In Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, there were 20,000 British subjects, divided about equally between the two colonies. The francophones of Canada in the St. Lawrence Valley formed 99.7% of the population. Obviously, these numbers made it impossible for the British to practice too radical a colonization policy. They had become masters of a French and Catholic country, but as the war was not yet over in Europe, it was possible that Great Britain would remain in Canada only temporarily. The number of anglophones was negligible and, until 1765, never exceeded 600 people, almost all military personnel having returned to Great Britain. In short, aside from a few civil servants, the country was comprised only of francophones and of Amerindians with scant knowledge of French. Subsequently, however, francophones would add almost no French immigrants to their numbers, while anglophones would see their population increase to the point that, around 1806, the two linguistic groups were about equal in number.

Treaty of Paris (1763) and North America

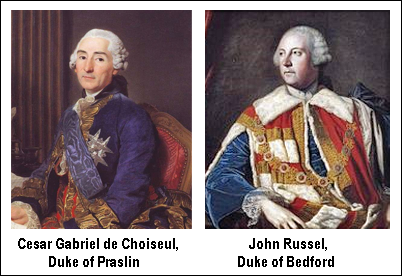

With the Treaty of Paris of 1763, which officially put an end to the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) between France and Great Britain, New France (with the exception of Louisiana) officially became a British possession. The signatories of the Treaty were the Duke of Praslin for France and the Duke of Bedford for Great Britain. From its immense empire in North America, France now possessed only the tiny islands of Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon south of Newfoundland. In the meantime, Louisiana had become a Spanish possession; in fact, on November 3, 1762, Spain had signed the Acte d'acceptation de la Louisiane par le roi d'Espagne at Fontainebleau.

In the Antilles, France lost Grenada, St. Vincent, Dominica, and Tobago, as well as Guyana, but took over St. Lucia, Guadeloupe, Maria-Galante, Desirade and Martinique. In India, France kept only five trading posts: Chandarnagar, Yanaon, Pondicherry, Karikal and Mahe, all of which it had been barred from fortifying. Great Britain got Minorca Island back and Spain recouped Cuba to compensate for losing Florida to Great Britain along with Canada. Finally, Great Britain obtained Senegal in Africa.

Thus the Seven Years' War was especially devastating for France: its military prestige was compromised in Europe, its navy much weakened, and its finances ruined. France retained mere scraps of its colonial empire in the making, most of it passing entirely into the hands of Great Britain. Although France was losing its first great colonial empire, few people at the time cared. Yet, for some historians, the loss of New France was, in the annals of France, "the greatest French defeat of all times." By comparison, the defeats of Napoleon appear as negligible.

According to the provisions of the Treaty of Paris of 1763, Great Britain would henceforth control an immense territory covering the Rupert's Land, Hudson's Bay, Canada (present-day Québec, all the Great Lakes, and the Ohio Valley), the island of Newfoundland, Cape Breton Island, Acadia (which would become Nova Scotia and New Brunswick), St. John's Island (Prince Edward Island), all of New England (the thirteen colonies) and Florida, taken from the Spanish.

Obviously, the Treaty of Paris served to confirm that Great Britain had become the greatest empire in the world and that henceforth North America would be English. The continent's new administrative framework was as follows:

The Province of Québec had been declared a colony (or "province") and its borders encompassed the Gaspé Peninsula (wrested from Acadia) and the St. Lawrence River Valley from Anticosti Island to the Ottawa River.

Nova Scotia included the region north of the Bay of Fundy (today's New Brunswick), St. John's Island, and Royal Island (today's Cape Breton).

The colony of Newfoundland included Labrador, the island of Newfoundland, and the Magdalen Islands, brought together so as to control the entire fisheries trade.

Rupert's Land remainded under the exclusive control of the Hudson's Bay Company as a "private colony".

There remained a huge triangle (the Great Lakes, the Appalachians, and Mississippi) designated as "Indian Territory", where it was forbidden to send colonists.

Despite everything, the French had managed to convince the British to let them keep their fishing rights off the Newfoundland coast (the "French Shore"). In agreeing to surrender the islands of Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon to the French, Great Britain was allowing the little archipelago to serve as a refuge for the French fishing fleet on the Grand Banks. During its history, the small archipelago of Saint Pierre and Miquelon was taken and retaken nine times alternately by the English and the French, and it was totally devastated with all its all inhabitants deported four times. It was not until 1816 that Great Britain finally ceded the archipelago to France.

Royal Proclamation of 1763 and language use

In order to provide an administrative framework for the newly acquired territories in North America, the Parliament of Westminster adopted George III's Royal Proclamation on October 7, 1763. Like all English laws, the royal proclamation was passed and promulgated in English. The French version had no legal value; it was merely a text translated for Francophones.

The Royal Proclamation demarcated the boundaries of the new colony, the "Province of Quebec":

Section 1

The Government of Quebec bounded on the Labrador Coast by the River St. John, and from thence by a Line drawn from the Head of that River through the Lake St. John, to the South end of the Lake Nipissim; from thence the said Line, crossing the River St. Lawrence, and the Lake Champlain, in 45 Degrees of North Latitude, passes along the High Lands which divide the Rivers that empty themselves into the said River St. Lawrence by the West End of the Island of Anticosti, terminates at the aforesaid River of St. John.

The borders of French Canada formerly extended from Acadia all the way to the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley. With the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the entire Great Lakes region was parcelled off and established as "Indian Territory." Although the British had "abandoned" the greater part of the conquered territory to the indigenous peoples, in actual fact it was because they could not ensure its defence. Better to temporarily leave territories they could not control to the indigenous peoples.

In any case, the colonial authorities were well aware that the situation was only temporary and that with the eventual immigration of English colonists, they could always dislodge allies who had become a nuisance. They also had to limit the westward expansion of the Thirteen American Colonies in order to encourage surplus populations to settle to the north in Quebec and Nova Scotia (which at that time included New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island).

The first English governor of the new "Province of Québec" was James Murray and, like everyone in that position, he spoke French well. Murray was to apply the British government's policy: turn Canada into a new colony by promoting English immigration and the assimilation of Francophones, by establishing the official state religion—Anglicanism—and by introducing new political and administrative structures in keeping with British tradition. At the time, such a policy was considered quite normal, and the French, Spanish, and Portuguese were not loath to use it in their various colonies, albeit with some difficulty at times. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 made provisions for the governor to convene a general assembly of the people's representatives when circumstances allowed (which was never done).

British Linguistic Policy

As early as 1764, James Murray established the first judicial institutions and decreed that henceforth "all civil and criminal cases" would be judged "in accordance with the laws of England and with the edicts of this Province." In addition, every employee of the state had to swear the Test Oath. In order to hold public office within the English system, one first had to swear an oath in order to prove that one was a practising Anglican. The Test Oath included four oaths: allegiance to the British Crown; repudiation of (Catholic) James II, pretender to the throne of England; rejection of the authority of the Pope; and renunciation of the dogma of transubstantiation (the transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ) in the celebration of mass. Although a Catholic might easily take the first two oaths, it was not the same for the other two, unless one could secure dispensations to permit the running of the country.

These measures were to automatically exclude almost all French Canadians (with the exception of a few protestant Huguenots who had stayed in the country) from public careers such as civil servants, clerks, lawyers, apothecaries, captains, lieutenants, sergeants, etc. According to the Attorney-General of the Province of Québec, Francis Maseres (descendant of a French Huguenot), the Canadians had to be assimilated:

It is a question of maintaining peace and harmony and of merging, so to speak, into a single one, two races which at the moment practise two different religions, speak languages which are reciprocally foreign, and are led by their instincts to utter different laws. The mass of inhabitants is comprised of Frenchmen originally from old France or of Canadians born in the colony, speaking the French language only, and making up a population estimated at ninety thousand souls or, as the French would have it from memory, at ten thousand heads of household. The remainder of the inhabitants is composed of natives of Great Britain or Ireland or of British possessions in North America, which at the moment reach the number of 600 souls. Nevertheless, if the province is managed in a manner pleasing to the inhabitants, this number will increase daily with the arrival of new colonists, who will come with the intention of taking up business or agriculture, so that in time it might become equal, even superior, to that of the French population.

The problem was that the much-desired English immigration did not occur (it happened only after 1783) because the new colonists made their way instead to Nova Scotia (formerly Acadia), while the Francophone population was growing quickly as a result of a very high birth rate. From the beginning, the British authorities expected soldiers to settle in the "Province of Québec" in large numbers and eventually assimilate the French Canadian population. But that did not happen! Moreover, history shows that, on the contrary, an all-male occupation army generally brings about the disappearance of the conqueror's language because language is transmitted by the mother (hence "mother tongue"), and mothers speak the language of the conquered. This is how the Normans (formerly Vikings) lost their language when they invaded France. In the case of Canada, almost all members of the military returned home, with the exception of troops stationed in the country, although a few Canadian women did, in fact, marry English soldiers.

Inevitable Pragmatism

As to be expected, it proved impossible for James Murray to apply the letter of English civil law in the "Province of Québec." Everything went wrong! Even the fur trade—the most thriving sector of the economy—was collapsing because it was no longer possible to obtain enough pelts from supplies in the Great Lakes and from the North. The institution of English civil laws threatened the French language and undermined French Canadian society. The Test Oath had excluded Francophones from the public service and subjugated them to the authority of a small Protestant and English-speaking minority (Montrealers). The requirement to renounce the authority of the Pope made it impossible to name a successor to the Bishop of Québec (who had died in 1760), dooming the Catholic clergy to extinction since it could not ordain new priests.

The situation in the courts soon became ludicrous. The population was governed by laws of which it understood not a word and, at trial, judges and juries were far too few in number to make any sense of the testimony of French-speaking parties. As a result, Canadians systematically refused to have anything to do with the courts or the civil service, thus leaving the door wide open for Anglophones to take the place of Francophone in the fields of communication, trade, economics, industry, and administration.

Contrary to the expectations of the authorities, assimilating Francophones proved impossible, the 500 or so English families being unable to assimilate the vast majority of the population. In addition, the Francophone trappers ("coureurs de bois") scattered throughout the Great Lakes region remained beyond the reach of the authorities, who considered them a "pack of vagabonds without faith or law." What's more, the governor noticed that the New England colonists were showing their displeasure more and more aggressively and demanding radical change. It was obvious that The English colonists of the Thirteen Colonies were very disappointed at not being able to help themselves to the newly acquired territories, especially since they had hoped to expand westward. In fact, this is precisely what the British authorities did not want. Rather, they wanted surplus populations to settle to the north—in Québec and Nova Scotia—thus enabling the assimilation of His Majesty's "new subjects" (Francophones). To agree for New England colonists to pursue their expansion west would be to concede that Canada would remain French indefinitely.

To make the Canadians a minority in their country, the British authorities had to be patient; Governor James Murray understood this and showed tolerance. Ignoring London's initial orders, he allowed the Catholic hierarchy to fulfill its priestly duties, exempted from the Test Oath those Canadians he needed for public office, and authorized defendants to plead their case in French by means of pre-Conquest civil laws. Murray's successor, Governor Guy Carleton, continued to practice an equally conciliatory policy with respect to Francophones and to seek their support, despite the indignation of the English population, comprised essentially of London merchants newly arrived in the "province."

Meanwhile, English merchants were beginning to run the colony's economy. In 1765, a petition addressed to the king by a group of such merchants demanded: "the establishment of a House of Representatives in this Province as in all the other colonies" under British dominion. According to the petitioners, only "His Majesty's old subjects"—Britons established in Canada—would be eligible. After all, the colony of Nova Scotia had had its own assembly since 1758! However, Canadians, designated "His Majesty's new subjects," took little interest in these demands, which would have barred them from Parliament. In any case, British authorities refused the merchants' demands. Instead, British companies set up shop in the province and behaved like new masters. The French merchants had left the country or been driven into bankruptcy by the requirement under the laws of Great Britain that trade be carried out within British companies. Thus after 1763, English would progressively become the lingua franca of "universal civilization" in Montréal and Québec City. English did not replace French in the daily life of French-speaking Canadians, but the French language of Canada slowly began to absorb new words introduced by His Majesty's "old subjects" (the British).

The English Conquest also brought Canadians the printing press and newspapers, which had been outlawed under the old French regime, but now contributed to the spread of the written French language. American printers Brown and Gilmore arrived in Québec City in 1764 and published the first newspaper, the Gazette de Québec / The Québec Gazette, a four-page bilingual newspaper supported by 143 subscribers. More than ten years later in June 1778 in Montréal, Frenchman Fleury Mesplet would publish the forerunner to today's The Gazette: La Gazette littéraire pour la ville et district de Montréal. Furthermore, Governor Frederik Haldimand (1778–1784), a Swiss Francophone (originally from the Vaud canton), founded the first public library in the country, which he set up in the former Episcopal Palace in Québec City, leased by the government; the library was bilingual.

Quebec Act of 1774 and linguistic duality

In the face of ever-worsening difficulties within the English colonies of New England, the British government needed to take measures to prevent the spread of autonomist tendencies in its Northern colonies. But the governor of the "Province of Québec," Guy Carleton, an Anglo-Irish aristocrat, seemed to have no great confidence in Canadians, at least judging from these remarks: "I like to believe that, if we could count on the population, we could hold the place. But we have so many enemies among this foolish people deceived by traitors."

Despite his lukewarm enthusiasm, Governor Carleton recommended to London that it take steps to ensure the loyalty of Canadians in the event of a clash with the Thirteen Colonies. Thus political pragmatism prevailed, and Governor Carleton judged it preferable to back Canadians rather than English merchants. In certain respects, he even became sympathetic to the Canadians' cause. He eventually acquiesced to judicial affairs implicating Canadians being judged under French law and Catholics being allowed to hold official positions.

On May 20, 1774, in the interest of political realism, the British government had the Parliament of Westminster adopt the Québec Act, a constitutional law designed to modify the status of the "Province of Québec." The law's full title was An Act for making more effectual Provision for the Government of the Province of Québec in North America. This law attested eloquently to the concessions made by London in its administration of the colony, in order to win the support of Canadians in the face of New England's increasing restlessness.

Section IV of the Québec Act decreed the revocation of both the Royal Proclamation of 1763 on French law and all the powers exercised by governors from 1760 to 1774. It marked the reinstatement of the "Coutume de Paris," that is, of French civil law. Faced with the difficulties of running the "Province of Québec" according to the laws and language of Britain, the British authorities finally relented, or a some might say, retreated. The Québec Act certainly represents one of the most decisive laws in Canadian history.

The new Constitution governing the "Province of Québec" significantly enlarged the colony's territory with the addition of the Amerindian zone created in 1763, a region in the north of the province stretching from Labrador to the Great Lakes area. Extending Québec's borders was a way for British authorities to assert control of the area from Labrador all the way to the Ohio Valley, including the hydrographic system of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence Valley. In short, Great Britain was restored to the "Province of Québec" the old borders of New France, minus Louisiana.

The constitutional act also reorganized the judicial system. French civil law was restored throughout the new territory, but in criminal matters, English law continued to apply. The Catholic religion was now officially recognized, allowing Canadians to accede to the magistrature and to other civil service positions. The Québec Act also abolished the famous "serment du test" (Test Oath) and authorized the Catholic clergy to collect the tithe. Moreover, the law recognized as legal the "régime seigneurial" (seigniorial regime) in use in the colony since the French regime. Nonetheless, London had not granted an elected assembly, fearing its control by the Francophone majority.

Since French as yet posed no problem, the Québec Act, following the custom of the time, remained silent on the subject of language. French was still the language of international communications and the Court of London sometimes utilized it. Moreover, high-ranking civil servants in the province were bilingual, as were all the English belonging to the upper classes of society. For many decades, all governors general were bilingual.

In other words, one might say that the Québec Act implicitly assured an almost official use of French, especially in restoring French civil laws (which were of course written in French). It was not deemed necessary to devote a specific clause to language in the constitutional document. In fact, it was primarily by means of this very ambiguous legal text that the defenders of the French language would later defend their acquired rights in Canada:

Section 8

And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That all his Majesty's Canadian Subjects within the Province of Québec (the religious orders and Communities only excepted) may also hold and enjoy their Property and Possessions, together with all Customs and Usages relative thereto, and all other their Civil Rights in as large, ample, and beneficial Manner as if the said Proclamation, Commissions, Ordinances, and other Acts and Instruments had not been made, and as may consist with their Allegiance to his Majesty, and Subjection to the Crown and Parliament of Great Britain; and that in all Matters of Controversy, relative to Property and Civil Rights, Resort shall be had to the Laws of Canada, as the Rule for the Decision of the same; and all Causes that shall hereafter be instituted in any of the Courts of Justice, to be appointed within and for the said Province by his Majesty, his Heirs and Successors shall, with respect to such Property and Rights, be determined agreeably to the said Laws and Customs of Canada, until they shall be varied or altered by any Ordinances that shall, from Time to Time, be passed in the said Province by the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, or Commander in Chief, for the Time being, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Legislative Council of the same, to be appointed in Manner herein-after mentioned.

In Canada, the constitutional law was well received by Canadians generally, especially by the seigniorial aristocracy, which saw its rights recognized, and by the Catholic clergy whose status was elevated. But it incurred the indignation of English merchants to whom London refused representation in the province while reinstating French civil law. On May 1, 1775, a bust of George III was unveiled to mark the coming into force of the new Constitution (the Québec Act). But to the astonishment of the crowd gathered for the event, it bore the inscription "Pope of Canada, Sot of England." It seems that some Anglo-Protestant merchants, angry with the sovereign, were to blame for this act of vandalism.

In any case, the anger of Montréal's English appeared a mere "irritation" compared to that of the New England colonists, whose discontent would culminate in armed rebellion. On May 8, the governor of Québec issued a proclamation promising "200 piastres" (500 guineas) to anyone denouncing the culprits, these "malicious and ill-intentioned people [...] having impudently disfigured the Bust of His Majesty, in the City of Montréal, in this Province." The culprits were never found, despite the promise of a monetary reward by authorities. The disappearance of this symbol of the monarchy was attributed to American troops that took Montréal in 1775.