The cantonal parliament allows all three official languages, but with fully 80% of the speakers, German clearly dominates. German and especially Swiss-German are the languages of parliamentary debate—questions and comments in either Romansh or Italian coming only now and then. Minutes of deliberations are in German only. As for laws, they are written in German, then translated into Italian and occasionally into Romansh (when they carry great importance).

In general, the cantonal administration operates in German, as do the courts. However, the administration responds in the official canton language used by the citizen in question. The canton has German, Italian and Romansh schools, and instruction in a second language is compulsory (Italian or French in German schools, and German in both Italian and Romansh schools). Communes decide on the language of instruction. Thus, Germans living in Romansh communes go to school in German but have full Romansh immersion, whereas Romansh speakers immerse progressively into German. Thus, Germans living in Romansh communes go to school in German but have to study Romansh as a second language, whereas Romansh speakers have to learn German progressively as a second language.

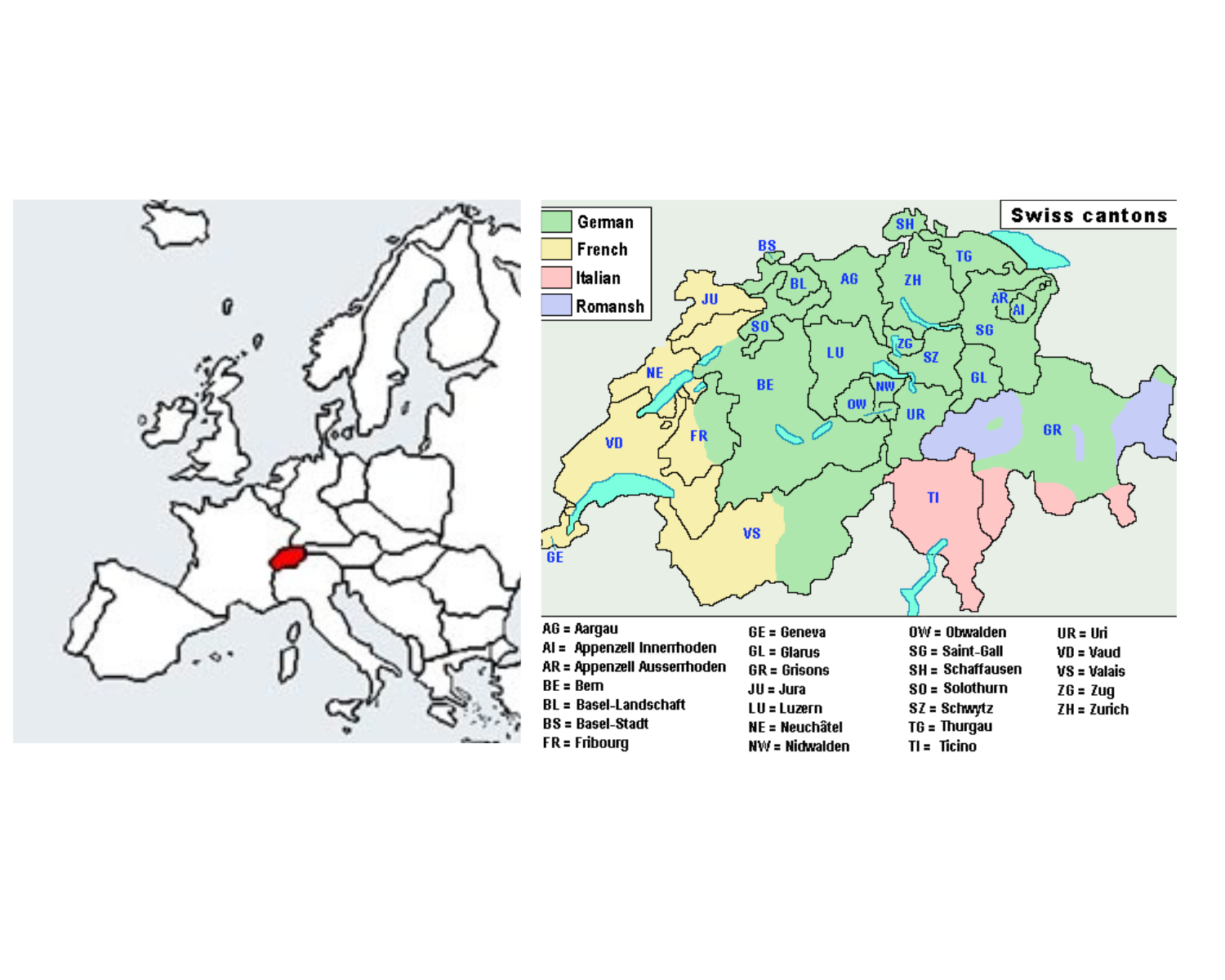

Through the territorial separation of languages, the Swiss Confederation has managed to protect its linguistic communities and avoid language-related conflicts. Switzerland is in fact one of the only countries in which territorial unilingualism can be applied, because the country's national languages are not imposed nation-wide. Clearly, this approach would prove harder to use in Canada, because its official languages are indeed in effect throughout the country, at least in principle.

The Canadian model provides a measure of protection for official-language minorities, whereas the Swiss model overlooks them. Again, Romansh in Switzerland doesn't quite have the same status as other official languages, hence the federal government's remedial action in its case, which is indeed a truly rare occurrence in Switzerland: as a rule, the federal government simply doesn't intervene in official-language matters. Romansh called for special measures because it was being neglected by those who should have been most concerned by its fate: the cantonal authorities in Grisons.

Its unavoidable pitfalls aside, Switzerland's language-management model has instilled peaceful co-existence among several linguistic groups in a single state, certainly a success for the country. And this type of success is rare. But this pax helvetica comes at a price: that of being governed by a German-speaking majority, and by politicians, bureaucrats and business moguls who think and decree in Swiss-German and who are driven by economic prosperity.